FLF initiated a much-needed debate on the prospects for local intervention in abandoned territories.

An opportunity for reflection on the future of development projects for mountain, inland or protected areas. Introductory document here. See also webinar of 08/07/24

We territorialists have interpreted History as a succession of phases of a superhuman (or at least overruling personal wills) breath that now brings inhabitants closer and now moves them farther away from places to inhabit.

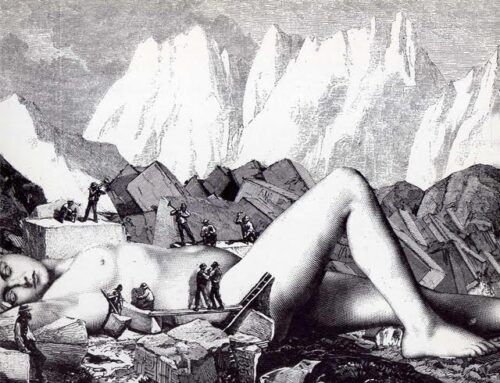

But in our time, in the fifty years of elaborating this sumptuous metaphor of living on Earth, we have only witnessed a gigantic, exceptional process of global deterritorialization. With different rhythms according to decades and regions, we have witnessed an uninterrupted flow from the countryside to the cities, from the mountains to the plains, from inhabited communities to individuals without neighborly relations.

Now, as a gigantic “lemming” migration of entire continents is on the horizon, in the European dimension urbanization is hinting at an end (mainly because the territorial reservoirs are almost empty), and we, who believe in a healthy metabolism of our world, are anxious to recognize the signs of the reversal of the process, the European “return to the Earth,” which our territorialist creed prophesies to us is imminent.

It is a phenomenon that none of our generations has ever experienced and therefore lends itself to being imagined in rhetorical forms. Fantasmi biblici e desideri di revanche urge us to consider as heroic returns every boy who resumes his grandfather’s peasant productions and every new occupation of abandoned rural houses.

In reality, the future, although most likely to be marked by a significant phase of territorialization, will certainly not reproduce in territorial relations the structural features of the past and will not tend to automatically generate the same social, political, and economic dynamics.

It certainly will not be culturally a “return” to the rurality we know and its community dynamics, and we can only predict that it will be fueled by a new and different approach to space and time, less concentrated but also less abstract than the urban one.

These considerations are easily arrived at if we rely on some elementary “Braudelian” deductions from the complex situation of our time. In extreme summary:

- The fruitful chaos of the neutral phase. Just as in the succession between El Niño and La Niña in Pacific meteorology there are periods of climate “neutrality,” so the reversal of the deterritorialization process of the 20th century will have a period of co-presence of weak trends in both directions, before flowing into a more intense flow of territorialization, driven by the unsustainability of cities.

In short, it is clear that a situation of concomitant pushes to and from the non-urban territory has just begun and will last for at least a few decades. In fact we are verifying concurrent thrusts in the physical use of land: on the one hand there will still be strong dynamics pushing to cities, mythically considered as the place of a thousand opportunities for self-improvement; and on the other hand there will be more and more experiences of rural efficiency, increasingly accredited to meet the demand for food, cultural and ecosystem services of cities in debt to nature. And again, in the behavior of the inhabitants: on the one hand, in many metropolises, areas of the urban landscape will be qualified, inducing a growing entrenchment even outside the LZs, even in certain suburbs that had fiercely housed as CIEs entire generations of bewildered immigrants; but on the other hand, this dynamic will be co-present with the irreversible abandonment of entire mountainous areas where depopulation will cause a total turnover of the inhabiting society, not only in people but also in the intangible, economic and cultural structures that had sustained it for centuries.

In this sort of chaotic interphase, at least one generation in Europe will not be subjected to a single overwhelming driving force, as has been the case so far with urbanization, but will be pushed in different directions by other local dynamics. In that storm, each will paradoxically be freer than now to undertake his or her own way of living, but also will be more alone in his or her enterprise, will have fewer references and models, given the weakening of both the urban and rural models.

- Culture and citizen values. I processi urbanizzativi e di pianurizzazione in Europa sono massicci almeno dal secondo dopoguerra. The result is that now in the vast majority we have been citizens for at least three generations. If the mass of migrants in the big cities of the second half of the 20th century were peasants, today only 10/15% of the millennials had direct family contact with the rural world, and in any case very few develop a self-awareness linked precipitously to non-urban identity places.

If the city does not bother to produce a “consciousness of place,” the School and digital technology also do everything to homogenize an egalitarian culture, without differential reference not only to places, their knowledge and roots, but not even to all the identity aspects of direct experience that hitherto were explained by reference to one’s local sociocultural group.

Let’s be clear: nothing against the sacrosanct battle to prevent any differences from diminishing the universality of fundamental rights, but it is a manifest weakness of our time that shared skills, tastes, and enterprises are increasingly neglected in favor of individual ones that pursue abstract, generalized performance standards. In short, by now each of us thinks and chooses with values, attentions and criteria generated by the systematic prevalence of the urban ecosystem of the last hundred years: generalist, ideological, poorly connected to place or community, with short horizons and an inability to manage long-term projects. With these premises, it is clear: the rejection of the city, which increasingly animates young people, is also a product of urban culture, individualizing and more ideological than concrete, and those who go to inhabit the abandoned mountain will not be used to being involved by places or communities that welcome them.

- Disappearing community habitat. So in any case, the values of the rural world, including the sense of community, are not known live or at any rate not what they spontaneously concoct with younger people: they are not their context.

The idea of “community” is at the expense: that remnant of the culture of the working, not just controlling, community, which the glorious tradition of the communes had brought as a hallmark of Italian history, has dissolved in the very urban dimension in which it was born. In cities, the opportunities of modernity in which a community aggregation could be reconstituted from common conditions of hardship, as in Fordist factories or in the ghettos of the newly built suburbs, were lost. Out of the cities come individuals, naive (in the proper sense of not feeling that they belong to a genus, a lineage) accustomed more to competition than to cooperation, investing more in personal identity than in common enterprise. But even outside the cities, community dynamics are disappearing, not only because of the thinning of inhabitant cores but also because the reasons for common operation are disappearing: largely mechanized peasant labor becomes individualized; the maintenance of balances with Nature in ordinary practices is lost; the care and use of common goods (water, forest, pasture, stores), when one remembers them, are delegated to institutions.

They still form, and not only in the rural world, reactionary communities, in the concrete sense of the term, of inhabitants aggregated by a reaction against a powerful common enemy that alters the land and landscape, that pollutes, that shuts down sources of employment, that plunders the common good. Steady on the political role of the battles, which are often won, it should be stressed, however, that reactionary communities end up depending on the existence of the enemy, with an inherent weakness that lies precisely in the difficulty of transforming the reaction to someone else’s project into one’s own, of overcoming NIMBY syndromes by recognizing themselves as actors in a community project based on the common resources and generally on the specificities of the area being inhabited.

- The individual escape from the cities. Without a community of reference, with its built-in rules and concrete habits that make one belong to a secular stream, the discomfort of the homines novi of our time, scattered and dissatisfied, becomes radicalized, in the very sense of going back to the roots and questioning the main nodes of the social contract underlying cities. It frontally challenges no longer just capitalism, but all consumerism (now clearly unsustainable) and then directly attacks labor: a hitherto untouchable taboo placed at the heart of the modern city.

The challenge, not proclaimed but implicit in the life choices of those who make them, is often so radical as to completely displace any reformist strategy based on a more equitable redistribution of the added values of industrial and digital production or on a unionization of labor relations, which are in fact ungovernable as a whole because they are now individualized.

Instead, the tacit and personal challenge points directly to the real primary resources of life: time and space.

Challenging labor “withdraws from commerce” time sold to the enterprises of others, now considered only wasted time for a wage that does not even free up “free” time.

The cost of such a simple and nonviolent act is unsustainable in the urban system, and can be met only by those who have already drastically reduced their consumerist needs, spontaneously adopting a lifestyle, a real “diet” of great sobriety and little blackmail by money1.

Making this regime possible are the even technological semi-free necessities of our time: the digital network, transportation, essential foods. These are endowments of basic services, the outcome of the constant proximity of the urban habitat even in the most remote places, so being a hermit today is much easier than a century ago: access at minimal cost to these services now constitutes the fundamental equipment for living in “semi-deserted places ma….”

By counting on these endowments and conquering work time to do “other” than produce or consume the superfluous, the attractiveness of urban space, which for 200 years has been considered the place of opportunities for employment and consumption, is also lost. The city, having dropped the attractiveness of the endless supply of labor, shows itself to be a trap to escape from for those seeking direct and unmediated contact with the “raw materials” of living: a place full of services largely not considered necessary, a center of social rituals experienced as constricting, with unsustainable rhythms and rents that weigh like burdensome taxes, with no free spaces.

It is likely that it is precisely the search for now masterless, virtually free spaces in which to nest in order to make it the new context of one’s free life that will probably be the most interesting driver of the new processes of territorialization. In that context, the work that engages hard to obtain directly and with consonant biorhythms the products of direct consumption takes on new flavor: the roof, by rehabilitating ruins; energy, by running the small water or windmill; food, by “eating the meadow,” as friends who have been busy for months contending with the forest on a mid-mountain estate have told me.

It is a trend, so far initiated by a few, but one that fully meets the requirements of “ethical territorialization” emerging in urban youth malaise. So in all likelihood it will be significantly present in the transitional period of the coming decades. In the most romantic cases in the background we glimpse the picture book of Robinson Crusoe read by kids, the Titian Terzani lecture. In many other cases those books on the table are approached by the flash drive for internet connection, a comfortable seat for a few hours of remote meeting a day, a beat-up 4×4 to get around.

In any case, in the first experiments of the “new living” we can already read some characteristics of the “foundation” phase. Indeed, as on the ship of Greek colonists sent overseas to build new cities, the new settlers travel light: no first and no third age. They need consenting, sober, strong, adaptable adults.

To children the settlers today think they can think as soon as they are a minimum stabilized; to themselves grown old the settlers today think they will think children grown old. So if generational traffic by “foundation site” is suspended in the next few years for new settlers, they will resume childbearing after that and after that they will think about teaching, healing, reworking rituals and culture. Only then will an active community really be needed.

These are the symptoms of a new air.

If we have interpreted them correctly, we must look carefully, in the chaos of the neutral phase, at the new colonization of the most abandoned territories that is starting in these years: it will be the result of a radical reaction to the structure of contemporary society.

Like all radical acts, it will be a choice accrued by individuals without counting a priori on the sharing of any form of community: to those who begin that journey of born states it does not seem urgent to equip themselves with cultural tools to get out of the individual dimension.

We, who belong to the culture that has believed it necessary to face the challenges of the world together and who have relied on communities and their implicit project, worry that these new subjects of territorialization lack the forces needed to address the gigantic issues that climate change and loosely centralized relations impose (from water management to the movement of goods and culture in a low-centered world).

We hope to be wrong, as it happens to parents who are reluctant to give their children the keys to the house, but in the meantime we try to make the work done to make the house usable for them as well.

2. The allure of territorialist research

We territorialists have over the years built a very good cultural machine for understanding the world and acting accordingly. We have moved from thinking about the complexity of the 1900s, but organized in order of the time and space that each person finds as the context of his or her life (life being, of course, the text of which each person is the author).

A dozen sharp and stubborn minds (Magnaghi, Gambino, Becattini but not only) have over the decades clustered a model of high craftsmanship research/action, which we might call “Gramscian corrected Bateson”: a cultural strategy with a territorialist perspective in which the logical steps of critical reason are appropriately mixed with other phenomenologies of sensibility, ethics and planning.

Dozens of passionate scholars have poured their disciplinary expertise into the hopper of that model, churning out a fascinating theoretical-experimental cocktail that allows us to explore the real and the possible with the most advanced scientific criteria but keeping our feet firmly on the ground.

Today, downstream from that creative phase full of continuous reshaping, we read the territorialist paradigm as a way of research (rather than a method) strongly influenced by the specificities of the territory, which invites to proceed each time reinventing itself, partly with deductive logic and partly with inductive criteria: from above and below, like stalactites and stalagmites when (and if) they meet to make supporting columns.

In the span of 50 years, this adventure of thought has materialized in various laboratories not only of knowledge but also of power: for example, with the drafting of spatial and environmental plans.

In the exercise of power (if only regulatory) difficulties continually emerge in the search for balances: between knowledge and normalization, between proposal and sharing, between experiment and good practice. Sometimes a preponderant phase of theoretical elaboration runs the risk of breaking through into an assertive having-to-be, into definitive rules that greatly limit the effectiveness of plans for the implementation and management phase. At other times, the “cold” result of data has been tempered with “dirty work” on the ground (as recounted by M. Rossi), in which shreds of collective memory are recomposed into congruent frameworks and inhabitants are gathered around relevant goals.

They also enjoyed successes in developing shared strategies, which, however, were the result of very strenuous paths with shaky results.

In any case, territorialist thought grew in the long post-war period at the end of the millennium, when the socio-economic and cultural aspects of our generations seemed consolidated and in any case at a low rate of change.

Today, the disappearance of the “founding fathers” coincides with the phase when territorial dynamics are taking on a new impetus. The driving forces transformative outlines sketched above open up perspectives that call for a profound revision of the research/action machine that has been broken in its time. To make it work best in the new historical contexts, it seems to us that at least three fundamental, interrelated aspects in power management practices need to be reset:

- The immobile structure. Work still needs to be done on the issue of structural interpretation of the territory, an important chapter in territorialist research, which drew on the best epistemology of the 20th century to make relationships prevail over things and to distinguish enduring connections from random or contingent ones.

That of structural recognition has been an exhilarating season, energizing an entire generation of researchers in the mirage of a universal key to pour into the territory the specialized knowledge of many disciplines, themselves already in turmoil over specific revisitations of reference paradigms. Thus one tries to intercept the young ecology that already gathers the natural sciences or history that with Braudel is being equipped to be “the common market of the social sciences,” starting with geography. Thus we try to insert into the structural framework of the territory the subjectivity of the perceived landscape, its identity ideologies or conversely the desire for exploration and being amazed that seem new dimensions of contemporary living.

Fascinated by the complex geometries of an integrated structural vision and the dizzying prospect of rereading the territory in a relational and non-objective key, open to serendipity and random nexuses and not just needs and causal links, we territorialists have been consumed for years in mapping networks and studying coincidences and overlapping phenomena, with great passion and enjoyment.

But the results have been mixed and especially the translations into design practices have been modest.

In “Spatial Plans,” the invoked plasticity of identified relational structures has often been reduced to a list of objects to be protected, lacking the planning to define rules that are about relationships and not things. And even where guidance for structural relationships has been attempted (e.g., those for environmental issues), the reference structure is defined with nexuses and nodes so necessary that they are cited in the regulatory section as “invariants.”

One reads the structure by relationships but then acts on things. It thus seems to drastically simplify all management processing but ends up communicating that the relationships coincide with the related objects (and thus brings everything back into the realm of heritage to be protected, as the “Cultural Heritage Code” does).

Institutions are urged to prefer the false equanimity of generalized norms and proceed by typology, with case histories métrisée 2, quantitatively defined or belonging to precompiled lists. This allows for a semiautomatic application of the rule, but makes any verification criteria deductive, and eliminates any local contribution of specific readings, much to the chagrin of the living process of shared recognition.

The input of the land becomes negligible in the very use of the tool that should recognize the specific characters of places. We are reduced to a purely defensive use of structural interpretation, aimed at preventing disruptions of the status quo ante, considered a priori better than the future state.

We are far from what we hoped for in the construction of the cognitive framework, when using structural recognition as the key to recovering a common knowledge and a vision of the inhabitants, if not communal, at least conscious of places, as we try to do every time with the ritual of Parish maps and “place assemblies.”

Between the cultural construction of the awareness of a place and the technical-institutional instrumentation to defend its fundamental characters, a furrow opens that reduces the continuity of community action and to its effectiveness in land management. On the other hand, the work of shared structural recognition that has been done in recent years has not triggered widespread and practiced know-how in those communities that would make any inductive process of “extracting” the value of places from places less laborious and uncertain. The value of places in the common sense (or community), that is, the reference that motivates essential choices, remains a kind of “cryptocurrency,” which theoretically is really an essence of the sharing pact of all inhabitants, but practically is reduced to an abstract representation of the intangible heritage that everyone says they share: a kind of theology of the common good.

The fragility of the structural construction is inherent in the contradiction between common knowledge and the operational technique of planners or the officials who manage the Plans; particularly regarding the rigidity of the identified relationships and their definition of “invariants,” which is useful to planners but harmful to the perception and common sense of the landscape.

In fact, in a tired phase of the dynamics of territorialization those aspects that seem to change little can be made the focus of defense against inconsistent transformations and “for futile reasons” (such as short-term private interests against common goods). In those cases, preservation of established structural aspects is certainly the best action.

But when we realize that we are in a phase of great change, the structure we need to recognize is not only that which is useful for defensive service, but above all we need to bring out that which can play an innovative purposeful role, which can give material and energy for the governance of change: we need a structural interpretation of the dynamics of transformation and not against them.

If we need a tool to inhabit change and not to complain about it, we need to take our conceptualizations back to their roots, and reinterpret the fundamental relations of our relationship with the land, making way for a more dynamic idea of structure, less patrimonial and more active.

It probably pays to “brush up on geniuses” like Jean Piaget, who 70 years ago (!) explored the cognitive processes of the different stages of learning (which he believed to be proper to all living things and special to humans) and studied their structuring not as hypostases of preexisting relationships in context, but as criteria of the interpreting mind, which progressively structures itself by organizing its own experience of the context and recognizing its recurrences, hierarchies, causal chains.

According to Piaget, it is structural a system of transformations that contains within itself the rules for continuing to keep itself recognizable in change3. Structurality is not a static attribute, of things, but a dynamic attribute, of the development of those who make sense of things.

For those interested in Territory, this conception of structure entails a fundamental change: if the “order” is not in the Territory but in the mind, we need to make ourselves aware of our subjectivity in considering the relationships between the things around us and between us and them. There are no a priori things or relations that are more important than others, but if anything, there are things or relations that we have long been accustomed to consider more important and have culturally hypostatized.

In the action strategies we identify in our life choices we almost always follow, for convenience, culturally shared sequences learned as tools for effortless decision-making. But this does not mean that we cannot modify these criteria of choice, introducing new ones or downgrading old ones. It is the recognition of a cultural option, of a different point of view, which in Art often happens and which concerns purely immaterial values and criteria, produced by our thinking and its sharing with the cultural communities in which we are embedded, and which falls back on the concrete part of the territory only in the actions consequent to those choices.

Thus, not a pre-existing structure, but shared structuring activity is the main agent for enhancing territories and is the only action that brings about effective strategic changes antagonistic to the trends caused by driving forces.

For example, without the idea of environmental networks and green infrastructure, a new structuring criterion for our relationship with Nature, today we would have no weapons to contain urban discomfort as a result of climate change; without the idea of landscape as a cultural habitat of everyone’s living, a new vision of the shape of the land and the right to live well, today we would not be able to contain the cancerous extension of the centerless suburbs.

In short, if we territorialists focus on a “Piaget-like” idea of structuring action, the goal of our research/action practices becomes clearer to us. We should perhaps call those cultural practices structure/action, since they involve the reconnaissance of cognitive and evaluative materials to be shared on the ground in order to decide the relationships to the things we consider important and how we and our children can enjoy them.

The very difficult climate debate teaches: there is no science that can be locked into a claimed objectivity and with it claim a foundational role in life choices. On the contrary, it is only a work of shared structure/action that assigns importance or not to those scientific indications in the cultural universe of the decision-maker. Whether the decision-maker is one or many a does not matter: what matters is the making its way into the decision-maker’s mind of a structuring consideration appropriate to the times we live in. And in democracy, the decision makers are all of us.

- Community as an edifying narrative

At this point the second fragility of our theoretical elaborations emerges powerfully: the role of community.

In our logics, the community is the sociopolitical locus of design awareness of the physical and historical context; it is that large group of inhabitants that can best interpret not only its relations with the rest of the world, but also the tensions that develop within it.

We postulate this capacity as a natural and widespread process, but we observe it to be activated only when the territory is “pummeled” with some violence worse than others: that’s when the Community takes shape, makes its wise voice heard based on a culture that is incontrovertible because it is experiential, and succeeds (sometimes) in fending off the attacks and foiling the threat.

In our narrative, the Community is a magical place, a kind of “black box” into which cognitive components and critical yeast are poured and come out, like noodles from the pasta-drawing machine, consciousness of place and judgment on different operational strategies for the sustainable development of the area.

La leggenda dice che noi territorialisti nasciamo per portare aiuto alle comunità. In fact, the story goes that sometimes, as in the Seven Samurai4, the community alone would not make it, and external inputs are needed: here are the Territorialists, useful professionals practically triggering a hidden and mysterious force within the community itself that, even if at the last moment, nonetheless takes a stand and organically opposes the danger of change.

Obviously, the reality is different: except in glaring cases, the inhabitants of the territories we would like to enhance are insensitive to the issues that need to be addressed before crises and reluctant to change their attitudes about the exploitation and waste of resources. Those in the territories end up thinking that the “Spirit of Community” is a puppeteer with little presence, and that every time one has to wait for it to return, pick up the threads and revive the puppets to once again act out a play by subject already seen to reestablish the status quo threatened by the bad guys.

Herein lies our contradiction: on the one hand we acknowledge the phase of great change that is underway, and on the other we refer to a community dimension of yesteryear, the one that for centuries ensured the staying power of the rural world’s long-lasting projects, but which today, precisely because of that long season of resilience, has reduced its ability to adapt to change to a few labored reactions to looming events.

Today, those who have ventured to make Territorial Plans know that Communities are not an integrated and coherent organism, but a social body that has internally and entertains with the outside complex dynamics that lead to often conflicting decisions, with power and management relations (badly) mediated by institutions. It knows that this instability leads to a kind of powerlessness especially with regard to long-term projects, which are now denied, then indulged in, then again put on dead tracks, depending on the group at the moment dominant.

Also for community action, continuing the search for alternatives opened with structuring interpretation, we have been trying (for the past few decades) to use important metaphors that Piaget himself and Bateson introduced more than 50 years ago in learning processes, borrowing them from studies of the biochemical and cellular formation of the living and again speaking of morphostasis and morphogenesis5.

In these terms with our communities so far we have not gone further than morphostatic actions.

In research/actions with local communities, we were able almost only to push reconnaissance into the practices and ideologies of the residual inhabitants, assuming their design capacity as either continuing traditional patterns or reactionary to the abuses of the urban model. We gave resonance to those who were resilient to the changes imposed by the dichotomous processes urban vs. abandonment, trying to strengthen its initiatives (those of returners, sustainable agriculture, typical productions etc.).

For those initiatives, brought by the most resilient inhabitants and young people who re-acquaint themselves with the still lively community structuring, the consonances of reading the territory and one’s own role foster processes of territorialization of even new forces, which form a beneficial evolution of the local community, without significant innovations.

In these virtuous experiences each time we have verified that it takes lasting commitment, good contextual knowledge and honest role awareness to induce a solid consciousness of place. These are energies that are needed for any morphostatic resistance battle but that in so many other cases the community cannot find in itself.

Where responsiveness is weak many are the causes of overall crisis in the face of change: too tired present inhabitants, too elusive, slow, inefficient promise of institutions, too modest engagement of individuals, too brief volunteer enthusiasms.

Thus, except in virtuous cases where a cocktail of active stakeholders, efficient institutions, tenacious and enduring volunteers cope, the active community we count on seems to be dying out. If the community is not there, processes of consolidation of territorialization initiatives are not triggered.

We are facing a mammoth case of “double bind,” the one from which we do not get out of with the known solutions, the one that for Bateson can generate, sooner or later, an innovative reaction: a morphogenesis of behavior.

But if we reflect back on our territories the wonderful examples of morphogenetic humans or animals that Bateson cites to show the overcoming of the “double bind,” we see that we will not get away with the tools of structured relationship with the context we know: it is overcome only by prescinding from the organizational patterns used so far.

Almost certainly there is a need to pick up our hats again and go begging for new competencies and skills, still like the campesinos of the “Magnificent Seven.” But certainly the new competent ones are not us territorialists, withering over papers and readings: rather the weak local communities will have to engage the new inhabitants of the empty territories, the fundamentalist no-communities outlined above.

In the absence of anything else, one must bet that they are the “salt of the earth” in this phase of chaotic change, and that a new perspective of quality of life comes from the synthesis of the two structures/actions, that of those who have remained on the territory in an increasingly immiserated group and that of those who come to the territory only, naive, homo novus in search of a new dwelling.

Today each of the two parties can only undertake weak structure/actions, otherwise incomplete in the face of the challenges ahead, according to the analysis made above. Probably the contribution of us territorialists is still needed, like that of mechanics preparing convoys leaving for long journeys.

Like them, we need to focus on the weaknesses of the equipment of both old and new settlers, and above all, it is a matter of doing unprecedented work to translate the structure/actions of each other, to find ways of pooling programs and communication/action among actors. It is about quickly activating that process of pooling and communication/action that has historically been slowly formed over generations to make community among the inhabitants of places. But we cannot assume that process of sedimentation as the canon of the new encounter, because the challenges of change do not allow it: we do not have generations to wait and we must quickly overcome entrenched mistrusts and prejudices.

In short, to achieve morphogenetic inventions and overcome the double weaknesses of the new territorialization, we must convince the remnants of resilient communities to cooperate with the new arrivals from the cities, lonely and clueless.

- Landscape as a commonplace

Landscape is a part of territory as it is perceived by peoples… Since the definition of Landscape in the European Convention we become aware of a verbal sleight of hand that is not matched by reality.6

We remain perplexed because the term “the populations” has a striking generality, which disregards being inhabitants, place, and time.

One might say that, to the triumphant sound of the Ode to Joy, a burst of Enlightenment electrocuted the Council of Europe and with the “optimism of the will” vainly set the Landscape to act as the universal glue of a thousand historically individualistic or even antagonistic countries.

Ma a far fragile quella definizione c’è anche altro. Here, in our root revision, we territorialists want to seek remedies for the Convention’s other foot of clay: perception, which of course is a tool of interpretation of the individual and is instead attributed to populations.

Thus is revealed, on the podium of Europe, a skeleton in the closet that we territorialists and we landscape architects have been carrying around since our origins: the unexplored relationship between individuals and the Community.

Those who have experienced the “dirty work” of accompanying the inhabitants of a place in vicissitudes of choices and power over the future know that perception is not a communal good but a personal tool, and that if anything, the communal aspects are the result of a collective work of structure/action downstream of perception.

It is also known that designing and deciding “downstream” from collective structuring work that has already been done and has established results is easier but also not very innovative.

Instead, with Bateson, we know that morphogenetic aspects emerge not from the institutional workings of putting hierarchies of perception into statute, but from a kind of short-circuiting, creative invention, of born states7 of the structure/action that arises precisely from the rational and sentimental fact checking of our perceptions of the context.

If we call insurgent those stages in which morphogenetic responses to “double-bind” situations mature (as M. Rossi proposes in the wake of the last Magnaghi), we must distinguish between social and political insurgence and cultural insurgence.

The first (that of Alberoni’s Statu nascenti) is born and developed in the squares, in a very short time, almost skipping the structure/action work and arriving at operational decisions with instantaneous processes of sublimation, in which awareness is a flash almost simultaneous with the thunder of action, merging for a moment individual and collective (to quickly fall back into a nefarious dichotomy).

L’insorgenza culturale invece è una partita complessa, i cui attori sono tutti individui che confrontano le loro esperienze (necessariamente percettive). L’insorgenza è storicamente il luogo dell’arte, della formazione di Avanguardie che (come dice il termine un po’ guerrafondaio) esplorano il territorio prima dell’arrivo delle truppe. It is urban individuals, bearers of cultural germs from outside the static community, who propose a different gaze, a way of perceiving and interacting that involves an innovative appreciation of Landscape and other local resources as tools to be used against new pressures from outside (from climate driving forces to speculative low-handedness of fashionable local productions).

In this perspective, cultural insurgence is in fact the undertaking of a conscious territorialization that gives rise to a new community, but it does not yet have the tempering effects, the gyroscope effects in the depths of the ship to stabilize the beckings and rollings, that the established community has always carried out to make the navigational course of our lives bearable.

The cultural insurgence of art always contends with the “possible consciousness” (to use a Maoist term) of the community of reference and provokes advances in the way we perceive the world.

As in art, this conscious territorialization activates a process (more or less long but never instantaneous) in which individual bearers of innovative behaviors metabolize the structure/action from the landscape proper with local ones, and from that synthesis, always surprising, arise innovative, morphogenetic decisions and strategies.

We territorialists, who would like to be the technical assistants of cultural insurgence, have to take care of that metabolization, the basic process of living, which requires an attitude that would be good to resemble the idea of care of the oriental disciplines, all to be studied and invented. Certainly it is a role that forces us to review our toolbox of researchers and didactics, to devise tools suited to the new subjects we face and the new stages of the territorialization process they (not we) face.

So far, this is a reflection matured over time and verified in the field.

But the urgency of interventions also brings into play thoughts that are not yet established, to begin to agree, with those who want to participate in this enterprise, new tools to be activated.

I believe that in recent years there has been a lot of good work done on the content and, on the other hand, a lot of backwardness in the way of communicating it, which has remained nineteenth-century (as this writing!). Now the problem to be tackled is mainly that of communicating to subjects with histories, roots, ages quite different from ours and, it seems, very touchy about formal aspects.

Reviewing communicative instrumentation brings up other contradictions and aporias, but discussing these would open another chapter complicated to decipher. Instead, it is necessary to proceed by small steps and frequent pauses for discussion.

Thus, to simplify we condense into a few provocative insights the instrumentalities we will have to avoid, since at this point in the research, with Montale, only can we say what we are not and what we do not want.

The guides of structuring. Our most compelling work, the one in which we most enjoy and in which we feel we really make a contribution, is to give an interpretation to the world we encounter, to organize it mentally, to take its measurements and vitalities. Why prevent this adventure for others? Why pass pre-packaged packages of interpretations like cruise ship tour guides?

To initiate the new inhabitants to be new territorialists with their splendid structures/actions the most we can communicate of ours are traces, fragments, fil rouge that we hope will prove as stimulating as the views of a writer, the glances of a painter or photographer, the archaeological remains of a vanished civilization.

Teaching maps.. The new inhabitant needs fascinating maps, not to return the obvious and reach the proclaimed destination, but maps to get lost in, maps that generate serendipity, which is one of the most enjoyable and stimulating acts of territorialization8.

Encountering unexpected things or people will, in the times of web and AI dominance, be one of the few remedies against homogenization (along with love and friendship).

The new tourist we are interested in will be passionate about these aspects, which silly maps threaten to spoil every day.

The virtuous map is likely to be variable and full of reports of ongoing activities, “Active Landscape,” artistic interpretation of places: in short, an invitation to go in person and meet there an irreducible and blessed diversity from the already known.

The museified heritage. The cultural slenderness (bordering on anorexia) of the younger generation is not only the result of laziness facilitated by Wikipedia but is also a reaction to the inflation of firm, historicized information, cluttering every path of unguided perception. On the other hand, younger people show an inordinate passion for events, for everything temporary, with a kind of “situationist” eagerness that seems to be the counterbalance of the rejection of museums. It is a condition of transition, reacting to the bulimia of knowledge in 20th-century education, which today seems to impose a drastic effort of innovation in the delivery of cultural content, so that it creatively interacts with a free direct perception of them, stimulating intense experiences that certainly do not derive only from nomenclature contributions.

Machismo design.. The strong sign in context, the designer’s stylistic signature, the formal novelty at all costs are symptoms of a design disease of our time, which offends the common sense of landscape as much as the violence of a dictatorship offends democracy.

Il narcisismo esibizionista delle “archistar” viene sempre più spesso spento dal disinteresse della gente proprio nei luoghi urbani che lo ospitano e certo non ha cittadinanza nei nuovi processi di territorializzazione. Widespread, continuous, shared and not shouted planning is required in re-inhabited places (with Roberto Gambino we had coined the “humble project” for the mountain landscape), all of which are prerequisites for facilitating a plural and enduring enjoyability of the resulting Landscape and a personalization of the experiences of living or visiting, these being new topics in the new project.

1 Diet in ancient Greek means “way of life,” with a much broader meaning than just dietary rule, and ( I think not by accident) in the early Middle Ages it also takes the meaning of official assembly, a day set aside to meet and decide (from Charlemagne onward). In both cases the meanings are important for a historical temper of new foundations, of basic reorganization of living, alone or in collaboration.

2 The awful French neologism nicely reproduces the horrible forcing of quality into quantity of any generalized definition of dimensional thresholds to segment continuous natural phenomena or functional (or aesthetic) relations of works of man.

3 Jean Piaget, Lo strutturalismo (1968) tr. it Il Saggiatore, Milan, 1971. Piaget is not interested in understanding whether and how context is structured, he is interested in investigating how, from the moment we come into the world, we equip ourselves to move ever more rightly in the changing context, adopting increasingly powerful structuring criteria as we grow. Studying the child in his or her learning journey, Piaget identifies stages in which the process of structuring knowledge moves from a phase of pure repetitive sensation to which one must adapt to a reflective phase, in which perceptions are related and generalized, to an adult phase, of awareness of one’s structuring action and its interactive use with the context.

4 In Kurosawa’s masterpiece film (1954), later remade as a western by Sturges in The Magnificent Seven (1960), cinematic history is made with an archetypal plot: a remote village bullied and plundered by a band of marauders calls for help from a lone samurai, who hooks up others like him to go fight and die for the locals, only eventually insurgent.

5 In addition to various texts by Piaget on “development” see Gregory Bateson, Toward an Ecology of Mind (1972), tr. it. Adelphi, Milan, 1977 and id. Mind and Nature (1980), tr. it. Adelphi, Milan, 1984.

6 The definition reads, “Landscape” designates a certain part of land, as perceived by people (in English: perceived by people), whose character results from the action of natural and/or human factors and their interrelationships.

7 Statu nascenti , Francesco Alberoni’s first and best study (il Mulino, Bologna, 1968), defines the initial and exciting situation of antagonism to institutions in crisis, a time when personal opinions are more likely to become “political” and collaborate in group decisions.

8 In Serendip (an imaginary city perfumed by the Orient) Horace Walpole in 1754 placed a story based on wandering in search of something one does not find, but instead finding unexpected and salvific things and people. In the 20th century, serendipity became the property of historical and sociological phenomena to provoke unexpected and positive consequences, and Arnaldo Bagnasco in a fine essay places it among the city’s drivers of attraction. (Arnaldo Bagnasco, Fatti sociali formati nello spazio, Einaudi, Turin, 1998).