When sensitivity goes through the 4 inch format. New professions to build bridges between practices of virtual reality and practices of living in the physical world.

To think wrong is to sin but often to get it right, said the master. So great pessimistic thinkers of the 20th century sniffed the air and warned us, long before we knew it.

Among the earliest was Benjamin, who eighty years ago was frightened by the technical reproducibility of works of art, whereby we lose the aura of reverence and attention that art commanded when it was unmistakably the product of unique toil and skill. McLuhan fifty years ago is sarcastic in noting that the medium is the message, i.e., that we capture information (and make decisions) more by the medium that conveys it to us than by the content conveyed. Lyotard 35 years ago defined post-modern as the new way of acquiring culture that is emerging: superficial and by fragments, rhizomatic (instead of deep-rooted, like the earlier model, of the modern). In the current post-modern epoch, the words intelligent (read or bind in, in depth), or comprehend (put together, bring together) seem to go out of use, and instead ephemeral and deconstruction advance: we shed blocking ties, establish new relationships, even if we know they last the time of “a door opening and closing.”

Thus, when the smartphone in the last decade overturns every communicative and cultural habit, making the search engine reign by syllables and memory in the cloud, it seems that the enlightened people of the 20th century smile sadly, thinking: I said it. But, as is always the case, reality is different, for better or worse: we are witnessing (as before an exodus, Arminio’s fine article in Doppiozero suggests) dynamics that partly confirm the predictions and partly exceed them in directions difficult to imagine even by the most visionary Philip Dick of science fiction.

To understand what is at stake we must assume the realistic assumption that the enormity of the change we are witnessing is comparable to that of the transition from hunters to farmers (from Cain to Abel), from oral to written culture, from rural to urban habitat.

For those who work on understanding and communicating complex issues, such as landscape, it is easier to read the epochal dimension of the change in behaviors induced by the smartphone empire, which quickly becomes a change in deep expertise, not only in operational skills but also in sensibility and sense of personal identity.

So I try to add, to the many aspects of this radical change already outlined by sociologists and philosophers, a structural criticality emerging from the practices of landscape and art enjoyment.

The simultaneous management of two realities, one of the body in the place where it is and a mental one that awaits the immaterial relationship through the smartphone, determines not only a risk of dissociation, but a necessary impoverishment of the relationship with each of the realities.

In the immaterial relationship, one renounces any deepening of knowledge in favor of its instantaneous speed, an exchange that is devastating to overall cognitive aspects. We become disabused of the craft of knowing, which is the practice of structuring relationships between information, particularly between incoming information and information already organized in memory. We rely, without letting our previous experience intervene, on pre-cooked structuring, processed by a literal search engine; we think we understand (carp) by reading the first three lines of the Wikipedia entry, which is synthesis made by others (good or bad: random). If we stop training the muscle of autonomous organization of information, our mind reduces the capacity to process personal thoughts and becomes only a neutral vehicle of stimuli from the outside going on the primary sensors: drives, instincts.

On the other hand, instantaneous reaction is the new commandment, imposing on our mental activities an uncontrolled speed that adds to the deconstruction of thought. We are driven to immediate judgments in which instincts and drives prevail rather than reflections and comparisons with other stored experiences. Good first! At that point it seems simple to decide: we need only a like, an emoticon (or a vote) to rank “our” position. A depersonalized clik that of “ours” has nothing left.

But there is another renunciation, no less serious, in the physical relationship with places. With the mind elsewhere, that being-in, which 20th-century philosophy recognizes as a fundamental factor in the sense of self, is disabled. It no longer matters where one is: we give up reinforcing our identity as inhabitants of a place. It is like losing our sense of balance, which makes us feel WE as we place our feet on a ground we know, where we are reassured by doing acts that are repeated, in a context we master.

It is not just a matter of giving up identity-confirming processes: we become disabused of taking cultural advantage of observing our surroundings. We no longer know how to grasp the eventual, the fortuitous that characterizes the urban habitat where our bodies dwell. We don’t wait for the unexpected, the serendipity of the city no longer exists because we don’t activate receptors: we don’t pay attention, we don’t exercise curiosity, and therefore nothing interests and entertains us about our surroundings. In other words: we no longer have a sense of landscape.

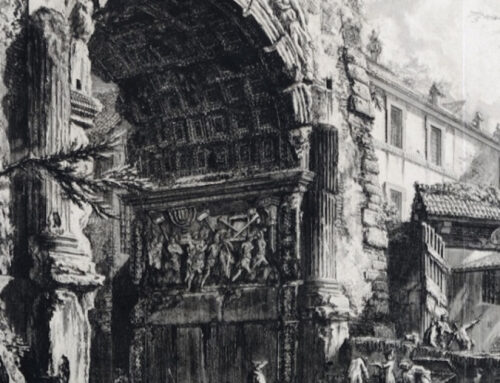

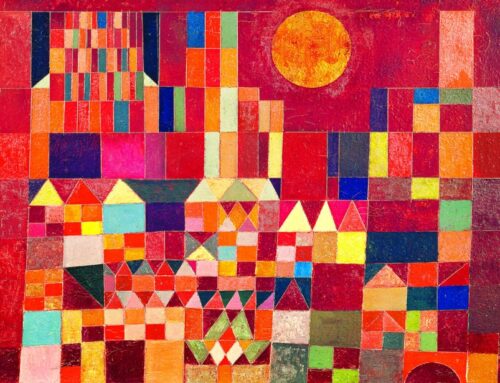

Concentrated on the 4-inch screen, where the most diverse images pause for a few seconds, our sensibility becomes specialized. We lose the holistic sense of presence in place and event, that confluence of senses that add to sight allowing the experiential immersion we remember when we say “I was there.” In the small, constant-size reproduction, one loses not only the aura of the artwork but also the sense of depth and proportion: the Nike is worth an earring, a photoshopped one is worth a Tiepolo fresco. In short, no convergence of senses and complex memory is stimulated, which are the raw materials underlying emotions: the ones that enchant us surrounded by Monet’s water lilies, that make us cry hearing music on a road trip, that make us come back happy and exhausted from a concert, that make us say that orecchiette pasta with turnip tops on grandma’s terrace is among the things worth living for.

If the smartphone cloisters deep emotions, the role of sensitivity is diminished. That integrated and trained sensibility, which had won an important place in our romantic personality for 200 years, is pushed back into the vexatious registers of the 1700s, reduced to an appreciation of pleasantness and cuteness: pooches and drawings for little girls, gossip and wimpiness triumph on cell phones. Art, which attempts to touch the trained sensibility, brought to the smartphone is lost, OK if it finds the distracted glance of those who browse for a few seconds through a catalog where Bacon, Haring and Morandi follow one another mingled with the latest photographer or videomaker.

If, as I believe, we are all moving to this non-exciting, non-identity non-place, if millennials have been inhabiting it since they were born, we cannot just do a battle of resistance and try to survive as we were and where we were. The smartphone, like all tools is a resource not just an addictive drug to the powerlessness of sensibility. We have to figure out how to treasure the resources that the new medium makes available to us and use them to rebuild the bridges between the two realities, as long as we can count on sensitivities capable of emotion, personalities capable of wonder, of acting reflexively and not on impulse.

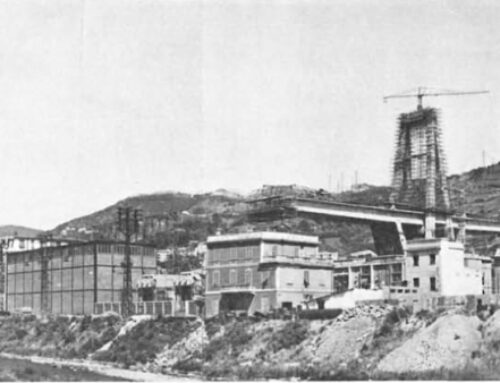

For example, we are trying to use the cell phone as an atlas, to make maps rich in images and documents referring to the places one visits, to get used to using virtual reality in support of the physical one and not as a separate entity. It is a new professionalism, in which we get curious and passionate about fishing in the infinite repositories of knowledge and bring fragments of knowledge back to the web stage, organize them and tell them geographically, so that they are well anchored in the physicality of places. This is work that we are proposing in the school-work alternation and seems to be of great interest to high school students. The New Engineer Bridges.