After 30 years behind the scenes, the issue of historic city centers returns to the forefront, because on the ground no battle is won forever and again threats of violent change loom over the heart of Italian cities. For as always the balance is lacking: too much and too little devastate. This time the killer is tourism, but the sheriff must be sought in the new inhabitants and new city users.

ANCSA is the glorious acronym for the National Association of Historic and Artistic Centers, which between 1960 and 1980 gathered the best of Italian land culture and captained it in the battle for the preservation and enhancement of historic centers, winning it. In Italy, it is the only postwar battle on land culture issues that can be said to have been won by the good guys: the one on landscape is still hotly contested, while on the suburbs it has not even taken the field. The battle was won by calling mayors and people to an awareness of the fundamental resource of the Italian territory: centers are the identity place par excellence precisely because of the sedimented signs of their history.

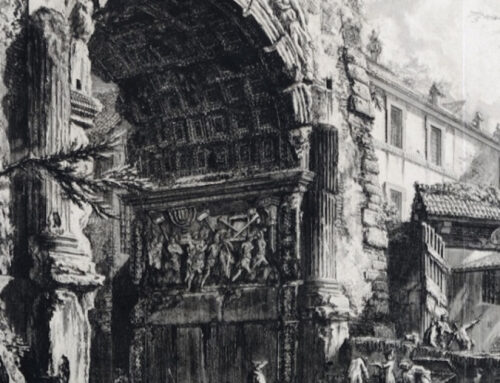

Since 1961, the Gubbio Charter, the founding act of the Association, has made us realize that our historic center is the most significant place of our identity, for each of us who inhabit the land of a thousand bell towers. This legitimized, politically and culturally, the introduction of special treatment for this piece of land, in times of the absolute prevalence of the convenient “equal law for everything,” which favored a false and trivial homogeneity of treatment in building the city. So, freed from the homologating rule, they invented the most diverse tools to deal with the problems not only of physical decay or functional obsolescence but also of the inadequacy of the photocopy projects that dominate the rest of the city.

However, it took decades before it became common practice to reclaim instead of demolish, to reuse instead of build from scratch, to pedestrianize instead of widening streets. It turned out to be successful to combine preservation with innovation, to integrate attention to walls and stones with care for social aspects (from housing for low-income people to funds for artisans and traditional stores), to value the particularities and design of public space rather than the homogeneity of buildings and the dimensional standard of services. The adjective “historic” has made it possible to treat city centers as a separate piece of land, with detail-oriented rules that are quite different from the ordinary rules of urban planning.

The battle of downtowns generated a long wave, which led to a broadening of the object of attention:

from the center to the city, from the city to the landscape. The place “center” seemed reductive for defining the territory to be treated with regard to its particularities, and ANCSA was again the forum where strategies were promoted for “the historic city,” then for the “historic urban landscape” (which were later collected in a UNESCO recommendation), and finally for the “historic territory” (to which Roberto Gambino dedicated the opening of the 50th anniversary conference of the Gubbio Charter, in 2011).

With the theme of “historical territory,” the horizon of the new challenge, opened by the European Landscape Convention, was shown, whereby it is not a specific type of place that is particular, but a generalized attitude of respect for the signs sedimented by history (not only human but also natural) and of appropriate planning, attentive to individual cases, that must be extended to the whole territory.

As always, broadening the horizon from the particular to the general fascinates understanding and makes any strategy of action ethically unimpeachable, but at the same time it reduces the clarity of the target and disperses positive energies.

Indeed, attention to the interpretation and design of the city and the historic area are well influencing the season of landscape plans and landscape projects, but on the other hand, historic centers are no longer on the agenda. They are now encompassed in an ordinary procedure of urban management, which formally maintains all the care now established by law, but is in fact inattentive to the new dynamics and transformative processes underway.

And the centers are not places of quiet, as it would seem if one looks at the troubled chronicles of the suburbs or the soil massacres perpetrated in the open countryside. Epochal changes are taking place in the centers, even if they almost always leave the walls and historic decorations intact. In the centers, citizens are increasingly only city users, while only outsiders now stay overnight there: poor people from other continents or tourists without a hotel.

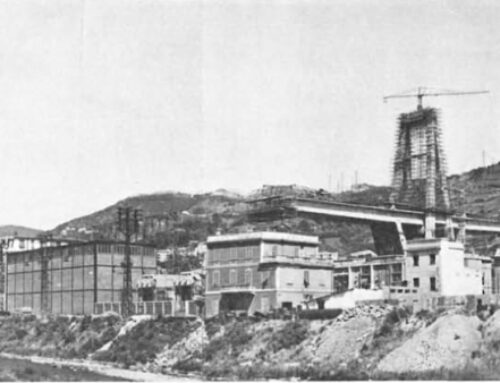

So ANCSA is mobilizing again: these days it is publishing a White Paper on the historic centers of Italian cities, in which CRESME has edited a statistical report on the recent socioeconomic dynamics affecting historic centers: housing turned into alberghetti, neighborhoods turned into ghettos. In the book, these phenomena are recounted in numbers from the 2011 census, but only a pale glimpse of the problem emerges, which has since multiplied to become a priority for the administrations of European tourist metropolises, from Barcelona to Rome, or cities besieged by immigration, as in Genoa or Madrid.

Transformations of users without physical changes have displaced administrations, accustomed to managing the inanimate, in the (false) hope that control of spaces would be followed by control of users, animated. Everything collapses when hundreds of apartments normally underinhabited by widows and students have magically transformed into thousands of rooms overcrowded with cheap tourists, awake 24/24 and active 7/7. A metropolitan nightmare, which the historic center apparently hosts “without making a dent.” It is the traditional residents who complain, while public spaces and homes seem effortlessly welcoming.

It is precisely this resilience that deserves reflection. For there emerges a structural property of the (historic) “downtown” that differentiates it from the rest of the area and gives hope for its future.

First of all, we must understand that what we now call the “historic center” was The City, in its entirety. In many cases we can read it perfectly, especially where, given its modest size, the ancient city has been preserved in all its parts and especially in its functional structure. Not a bonsai tree, but a seed, a city DNA, which contains all the essential elements of Italian identity, which then corresponds to a small town community, which puts part of its work in common (in the municipality) and participates in its management. Somehow this deep identity reference remains, and not only as a memory for the inhabitants for generations, but also as a visitor’s fascination: the historic center in many cases is the only universally recognized factor of cultural landscape, so much so that we now have to study strategies to thin out the tourist influx in the renowned centers, while no one visits the thousands of monuments and museums in the area.

Then the history of the center must be told, what has happened there over the decades and centuries: its changing users, the enormity of traffic and services for the area compared to normal residential functions, the filling up and emptying out like a sack period by period, the wild reuse of containers (in occupations, disasters, wars), and above all its making and remaking itself. For like the phoenix the Italian historic center is reborn from its own ashes, from abandonment, from destruction. Even today it seems obvious to us to remake the center of Amatrice where it was and as it was, even if it is technically almost absurd. On the other hand, the inertia of rents makes it seem obvious to build skyscrapers downtown, even though it is now almost absurd, urbanistically.

The power of downtown continuity is thus both asset and damnation for those who run the city: transformative pressures, including reconstruction, are very strong and often win out.

In short, we must accept the fact that what we see is never an authentic complex, as it was made in a primal act, but that the historic center is like Argos, Jason’s vessel, remaking itself on a voyage, the experimental site of continuous contamination of uses and settling of spaces, the site of the most unprecedented interactions between different cultures and functions. In short, the historic center is the ideal gymnasium to exorcise the fear of transformations, where to ascertain identity continuity far beyond the constancy of behaviors and the permanence of walls.

If resilience and the ability to experiment with interactions and cross-fertilization are the hallmark of our centers’ history, then we can also design a strategy to deal with these new tensions, not being afraid of new things, rather aiming for them. Airbnb fever will pass and a new model of center users will settle in, but we must involve them in their holding, which cannot only exploit a millennial resource, but must participate in the process. We must prevent the center from becoming a place where we freeze the status quo, where the rents of those who are already there prevent the actions of those who could be the new users, where we try to stop the flow of history, as happens with historic centers that become museized, or that become the business center of the modern city. We need to foster those who come to inhabit or use these places aware of a role as innovator, of the responsibility as sailor on Argo, where as you travel you have to participate in adjusting and modifying the ship so that it keeps the sea to the destination, that is, so that the center offers itself to future visitors and inhabitants as rich in charm as and more than today.

In short, to summarize in a slogan, “history leads us to favor those who deserve the center, because they show that they have a project in their favor.”