The emotion continues, and we are unable to process the earthquake calmly, while the project to re-inhabit the destroyed towns requires lucidity and disenchantment, to find the way between the alienation of new towns and the unrealizable utopia of perfect reconstruction.

By some very ancient malady our collective memory is full of removals of serious events, which, as Sigmund teaches, we do not remember but continue to hurt, even more so the more we persist in denying them. Thus one of the worst disasters of the past decades, the AFTER L’Aquila earthquake, about which very little is reasoned today, generates understandably absolutist but nefarious reactions in the harried statements of the authorities involved in the new earthquakes: “ we will redo everything as it was and where it was” (implied: “not as in L’Aquila”). Already for months, a chorus of technicians and intellectuals has been reminding us of the need for a technical-scientific revision of the concept of preservation, getting us out of the false alternative between prefabrication and superintendence (e.g. Elena Granata’s fine article on the recovery-conservation blog on September 7).

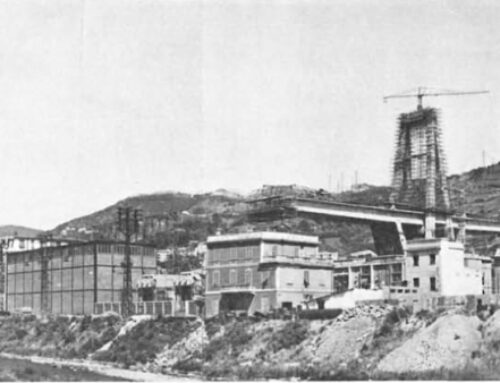

Let’s start from the conclusions of that phase: new settlements are deadly for the sense of community of those who try to re-inhabit the devastated places, but the photocopy remaking of old hamlets, feasible only with long timescales (more than 10 years), high costs and alienating effects (Granata speaks of parodying facades remade as they were with new houses behind), is also ineffective in restoring vigor to the affected communities. Post-earthquake managers and technicians need to be convinced to adopt different criteria: faster, effective for communities, long-lasting, less costly and therefore repeatable. But the suggestions made so far do not cover all the requirements; in fact, they appear contradictory, favoring one at the expense of the other. Sure we need to think about the systematic use of more resilient materials, such as wood or metal, but we do not control all that goes with it for the appearance of buildings; sure we need to locate more securely (assuming we can establish it), but we do not know all that goes with it for the memory of places….

A route out of the impasse can be charted by resorting to the methodological outcomes of the debate on landscape projects. For some years now, the idea has been consolidated that the landscape is a holistic reality, that is, perceived in a unified and integrated way, partly material but largely immaterial, linked to the perception and memory that the community (of those who live in or visit it) has of its territory. It is a reality in continuous transformation, moved by two engines: that of the physical modifications of the territory and that of the new and different modes of the inhabitants’ gaze and memory, which proceed unceasingly, influenced by the general cultural dynamics and variations in community composition. Generally speaking, transformative processes are very slow, especially cultural ones: we realize that the landscape has changed only when we remain absent for a long time and retain a stereotyped and immobile image of the places (and people) we know, highlighting by comparison the “violence” of newness.

Designing landscape improvements with these references means placing the planned changes within the more general and overall picture of places and the sense attributed to them by the inhabiting community, and measuring the quality of the project by the overall appreciation of places after the interventions. This involves an awareness on the part of the designer of the body of values on which he or she is intervening: both the physical places and the community’s consideration of them.

By this criterion, any project that affects common places, those that constitute the identity landscape of the community, is also responsible for the changes on the sense of landscape that it induces on the community.

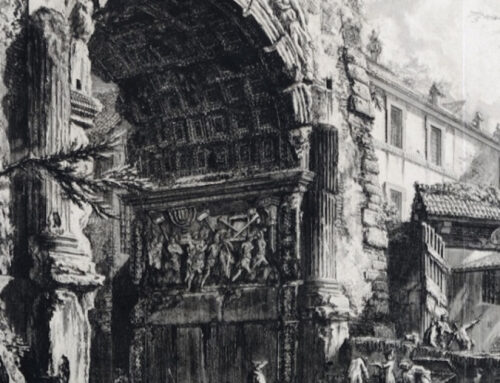

It is necessary for planners to know the structure of the landscape on which they are acting: the fundamental relationships that define the identity of a place, both physical and in the memory of those connected to it. It is a matter of understanding the role of what Marco Romano calls the collective themes: the church, the square, the gate, the theater,….cardinal points of identity. But above all, the ensemble aspects that give definite meaning to that place must be extracted. They are few but essential: certain dimensions and characters of the perceived space, certain relationships between collective themes and the ordinary fabric of the built, between built and green,….

Everything else is constantly changing, has changed in the last centuries and will change in the next.

In these terms, the disaster left by the earthquake is no different from the one produced by the unconscious scars of the suburbs, the warehouses lined up like TIRs out of doors, the banks adorning postwar cathedral squares: these are blind and deaf forces that have altered places but especially their role in the community’s sense of local landscape.

If master plans had been based on such reasoning, we could have avoided the disasters of the built environment. But it also applies to the destroyed: if you study the structural requirements of the shared sense of landscape of Norcia, or Amatrice, you can get less than 10 rules, to be respected, leaving for the rest freedom to experiment on all other performances (safety, economy, speed of construction, environmental sustainability,….).

They will be different rules place by place, to be worked out with the participation of experts but also the inhabiting community. They must be the result of a process of reappropriation of abandoned places, first sentimental than material, which can take place in the form of an event, even very quickly. For example, a well-prepared full immersion lasting two weekends, one to sow, the other to gather ideas.

So interventions to remedy these disasters will come from an awareness of the role they play: everyone will know that they chose to rebuild stone by stone those five buildings because they are important in the centuries-old memory of public space, and one will be proud to spend a mountain of money to get that common good back. But at the same time people will know that the row of houses on the major axis will be rebuilt with no constraints except a maximum height, a certain alignment and a certain ratio of walls to windows, but that on the ground floor there will have to remain spaces suitable for the new needs of commerce. Or that at the edges the houses may be different from the current ones but still maintain the appearance of continuity of the built-up area, as if they were walls that distinguish the village from the countryside. Or vice versa-it depends on what will result from those days.

It is a mode of participation, which the control engineers must also respect, because it is respectful of the history of the places, today also made by the earthquake, which in any case will leave indelible traces by modifying the landscape and its meaning, but leaving a stronger community, precisely for having guided its own identity through the hardships of physical destruction. As Bauman enlightens us, “A happy life is achieved by overcoming difficulties, facing problems, solving them, accepting challenge. You accept a challenge, you do your best and strive to overcome it. And then you experience happiness the moment you realize you have stood up to difficulties and fate.”