These days in Padua and in a dozen places scattered throughout the Alps and Apennines, a thousand scholars and enthusiasts honour the mountain builder, celebrating the third world meeting of Terraced Landscapes (http://www.terracedlandscapes2016.it/).

Since the early Middle Ages, for ten centuries a few dozen generations of mountaineers have built hundreds of kilometres of stone walls containing the land. A hundred boulders to be artfully stacked in order to have the space to carry a cubic metre of earth, and obtain a cultivable square metre, on the mountain slope. It is two or three days of hard work; if you do it a hundred times you get a hundred cultivable metres: the size of a vegetable garden. The vegetable garden, however, produces if there is plenty of water, and to get it requires other work, often even more arduous and difficult: the irrigation canals in the mountains are kilometres long, often dug into the living rock, with acrobatic paths serving small communities.

It is impossible today to realise the interminable toil that marked the centuries of settlement in the Italian mountains. They were not forced labour, they were ways of life, rules of behaviour, of the relationship between private and common, between fathers and sons, between men and women.

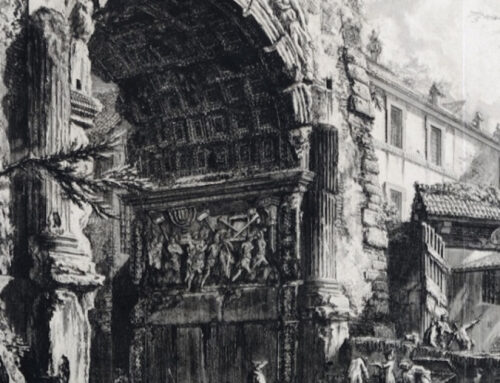

If you go up behind Piazza della Nunziata in Genoa, you walk along an avenue that leads to a princely palace, which towers over an entire valley with over 35,000 square metres of rooms and galleries. This is the Albergo dei Poveri, an incredible charitable institution founded in the mid-1600s by a group of nobles delegated by the Republic to help the needy. It is just one of thousands of initiatives by the wealthy Genoese who have made the Superb city strong and beautiful over the last four centuries. The first porticoed gallery of the Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno lines hundreds of tombs of notables, including recent ones. On each one are engraved in great detail their munificent commitments to give quality and services to their city: charities, theatres, hospitals, roads, wharves and libraries. And the same goes for the affluent bourgeoisie in Milan, Bologna, Florence.

It is impossible today to realise the dedication of the entrepreneurs that marked the construction of the Italian city. They were not speculation or investment for their own profit, they were ways of life, rules of behaviour, of the relationship between private and common, between fathers and sons, between men and women.

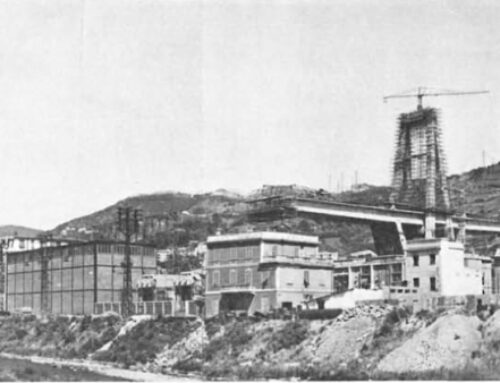

Why is it that today we cannot even conceive of a social sense of belonging like that which those urban or mountain landscapes testify to? Why does it seem impossible to us to desire lives that are not selfish, not dedicated to our own personal success, but to the success of larger undertakings that cannot be tackled alone? Yet the stones are there to tell us: cultivating mountains, building cities are actions of entire peoples, requiring a sense of self in the service of others, of the century and of life that we have now lost. By now, we use the rhetoric of ‘great works’ as a ploy for small short-term gain, and the parts that are being built seem almost more likely to be assailed by fraudulent lusts than to initiate a new, lasting reality. It is as if the future were closed to the next few weeks, as if we were no longer capable of projecting ourselves beyond a few months.

It is the long project that we are missing, the one to which we belong and which does not belong to us: the sense of being part of an uninterrupted flow of energy and care, which goes beyond our life and our strength, of an enterprise that directs us, but above all our neighbour, towards a better future.

And here we understand the causes of the lack of success of the long project in our time: because it forces us to devolve personal ambitions to a collective enjoyment, of generations to come, of citizens as a whole. When the payback time of one’s actions goes beyond one’s expectations, one’s life, one must think that one’s commitment is gratuitous, anonymous, dissolved in history like salt in soup. […] […] […]

Yet today there is an active and vibrant people of the long project, making the terraces and cathedrals of the third millennium, free and anonymous. It is a people that adheres to the ethos of the networking environment, open source and sharing. They participate in the long project without theorising about it, often in an almost unconscious way, but practising a continuous work of improvement, innovation and uninterrupted reconstruction of information that now constitutes not so much a job or a business, but a way of life, of rules of behaviour, of the relationship between private and common, between fathers and sons, between men and women.

It is a long, libertarian and progressive project, which brings together the goodwill of those who think that intellectual enterprises are part of a common good available for the contributions of all, just as in the free communes it was thought that the city was a common good available to those who wanted to inhabit it, and in the mountain that was being terraced it welcomed those who participated in the corvée for the community and carved out their own land with their work.

They are almost all young people, among the few who do not have their eyes unfocused, who care little about looking for someone to offer them a salary, who are not obsessed with visibility and success, and who conversely consider it obvious not to pay rents and not to be paid for the rents of their intellectual products, who work intensively in endless networks to enhance free access to information, knowledge, and tools that promote skills.

As with the city and the mountains, one adheres to a long nondescript project, made up of faith in the goodness of one’s tools, of hope that the goodness of the means alone will lead to optimal ends, which perhaps only others will see.

And to those who might not think that this story is about History but about vulgar rural, working-class or post-industrial labour, we must remember the great tramp of Trier, who was convinced that hope is precisely that force which redeems the proletarian and assigns him a project role in History. And if it does not seem that we are talking about cultural projects, we must remember that the first architectural notebooks concern cathedrals and do not contain drawings of arches and spires, but of machines for lifting loads and cutting stones.