Abandonment, one of the great themes removed for decades from the table of discussions on land and environmental governance, finally finds someone who discusses it, and puts it at the centre of projects. The mountain is the privileged place to rethink a postrural way of living, which is increasingly urgent to experiment.

On 22 and 23 May, two important associations that look to the territory (the Society of Italian Territorialists and Dislivelli) met in Bardonecchia and Turin to explore the theme of Return to the Mountain. A week earlier, in Demonte, near Cuneo, a group of students specialised in restoration and conservation, meeting in the association Campo base 1000, presented their project for the rehabilitation of an abandoned nucleus, as a model for Re-inhabiting the Mountain, sketching out a method of intervention suited in particular to the ‘middle mountain’, the most forgotten.

After 30 years of oblivion, in which mountains were only spoken of to denounce devastating processes of abandonment or territorial violence, today an active, non-nostalgic and future-oriented attention seems to be awakening.

They are isolated and fragile start-ups, but full of planning and innovation, only partly marked by the heroic desire to win with their own forces against immense historical processes. In fact, the generation of young families who, with a Protestant ethic, abandoned the city to resist in isolation at altitude is being surpassed. The new projects are more thoughtful social constructions, in which economic sustainability is studied on a par with environmental sustainability.

The romantic challenge of the Promethean enterprise, of inhabiting rejected places against everything and everyone, is gradually giving way to projects of organic land use, shared at least by a group of mountain users and progressively more widespread.

In perspective, the mountain is being thought of as a part of the overall social fabric, no longer just as another clean world, antagonistic to the vices of the plains. But in any case, the imprint of traditional sobriety and essentiality necessary in the previous phase of ideological resistance remains in the new projects.

It is precisely in the landscape that the profound structure of living in the mountains remains, resilient to abandonment, to ideological manifestos, to the passing of generations that are less and less tied to farming traditions.

The structuring factor of living in the mountains is a knowledgeable relationship between man and nature. It is a knowledge that is consolidated in direct, tiring, daily experience, which for centuries has been practised in work, but which continues in the alpine style of the climbers, dear to Messner. It is a knowledge that permeates the way of being, that crosses cultures all over the world, mobilises for solidarity with the Nepalese people terrified by the earthquake and makes friends among the natives of Machu Picchu.

It is based on certain unfashionable principles, which constitute a kind of lifestyle:

– the humility of placing oneself in a fundamental relationship with nature, constantly aware of its fundamental predominance, which the way of living must as far as possible support and not oppose;

– the tenacity of the endeavour, which requires for both work and ascent a constant and lasting process of action, never hasty but never giving up;

– the strategy of the collective, a distributed investment in the community, necessary to cope with the arduous task of managing a hostile nature and capable of activating an effective system of solidarity in frequent cases of emergency.

Today we still distinctly read these principles in mountain dwelling places, whatever the recent evolution they have undergone.

In fact, as far as humility is concerned, the landscape designed by man who inhabits the mountains is in any case like a cut-out inserted in the landscape designed by nature: so much so that the common sense of places is offended when man’s mark prevails or stands out as overbearing with respect to nature.

On the other hand, the exacting and constant care of the places (from forest containment to water regulation, from slope consolidation to roofing) jumps out at us now that the rhythm of maintenance, traditionally slow and tenacious as the mountain pass, has ceased. To our eyes, the traditional mountain landscape is only made lively by the action of the peasantry, and it appears dead if this is missing, so much so that the reconquest of the forest on cultivated land or between houses takes on dramatic and negative tones for us even though it shows a superb vitality of the natural ecosystem: it is the sign of the failure of the enterprise of living.

Finally, in the mountain landscape the sign of settlement as a common good stands out, and everything tells of shared norms and habitual corvées carried out for inhabitants and visitors alike: the huddle of buildings is devoid of fences; the few specialised buildings are linked to common practices: the oven, the fountain, the church; the paths and regulated waters are traces continually retraced with the work of all; the work of the forest and grazing is still organised on a community basis (so much so that in Val di Fiemme the forests belong to the Magnifica Comunità).

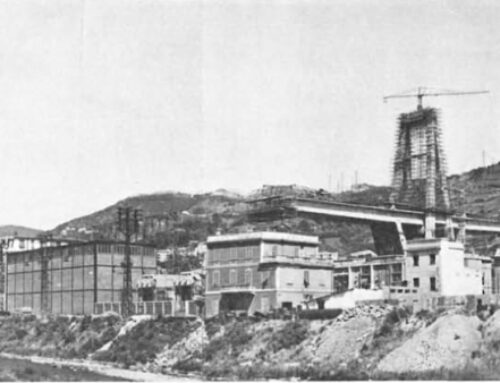

If one keeps in mind these fundamental principles, unwritten rules but engraved in the ethics of those who inhabit the mountains, it is possible to explain social dynamics that would otherwise be difficult to understand. As with the spread of the ‘happy degrowth’ model, which alludes more easily in the ‘internal areas’, non-urban and without intensive agriculture, in predominantly mountainous Italy. Or as for the mobilisation animating the civil part of the NO-Tav protest, consolidated in the valley section and totally absent in the other sections. In the mountains, a reaction of closure in the face of exogenous modes of intervention is easily predictable, not so much geographically as in cultural and anthropological terms. In fact, the discussion on the railway project has developed on themes and in ways that are completely incompatible with the reference values of the inhabitants of the Susa Valley. When the environmental and landscape problems emerged, the focus was on forceful or mediating solutions such as minimising damage or monetising it: languages that one is accustomed to in the plains, but totally alien to the principles of sobriety, humility, tenacity and a sense of the common good.

On the contrary, the programmes for re-inhabiting the mountains that are being discussed these days are animated by a spirit that is entirely consistent with the spirit of the mountain landscape:

– environmental and economic sustainability, perhaps only in the medium term, but lasting and resilient, based on a plurality of income sources (balancing agriculture, soft tourism and sporting activities) and on a radical optimisation of consumption, and above all on the involvement of young forces to build and work, as well as to live and use the sites occasionally

– strong interdisciplinary collaboration in the programme and intervention, including agronomic and environmental skills, historical and anthropological skills, and the technological skills of good building; an organic whole, which seeks integrated solutions for locations, maintenance strategies, and the exploitation of local specificities to invent new uses and new productions;

– rigorous sobriety of architecture, adapting where possible and reconstructing where necessary, with innovative but appropriate and site-specific technologies, where continuity with the pre-existence is a fundamental part of the project and to obtain it, it is not so much restoration canons that count as a reinterpretation of the identity relations between the parts of the natural and manufactured landscape, of the dimensional grain and materials of the new interventions.

Thus the new projects bring out from the most abandoned territories the deep structures of the landscape, a source of innovation and renewal, like Roman vestiges for Renaissance artists. The mountain continues to teach.