Dwelling in the sacred: getting lost without seeking meaning – Attention to the sacred in the landscape – The space of the psychological sacred and the sociological sacred – From discovery to the factory of the sacred

Dwelling in the sacred: losing oneself without seeking meaning

‘Behind the Landscape’ is the title Andrea Zanzotto chose for his first memorable collection of verse (1951). It seems that the poet’s tension is to bring (or bring back?) to the word the deep motions of the soul that the landscape generates for him. The ‘outer’ landscape as a provocateur of an exploration of the ‘inner’ landscape.

The adverb chosen is fascinating: ‘behind’, used as if to allude to a ‘behind the scenes’.

With this ‘behind’ we seem to understand the reasons for one of the disorientations provoked by another poem: we find ourselves, every day, normally, in the world beyond the high hill that the gaze excludes; sometimes we stop and wonder what is ‘behind’ that hill: there is the young Leopardi meditating.

Behind the landscape there is someone who perceives something different, something that sets in motion a sensation, a not very distinct but intriguing thought. Behind the landscape there is someone who gives a new sense to the landscape itself: new to him, different enough to shake off the sediments of habit and bring stimulating thoughts and sensations to the surface of his consciousness.

Certainly this is a psychological event that has happened to each one of us: a desirable disturbance that becomes the emergence to consciousness of something more, something unforeseen, something uncoded; it frightens and makes many uncomfortable, but for the most part, if we know how to make it happen, we seek it out.

The directions taken by our ‘consciousness-raising’, starting from a reflective look at the landscape, are not always the same: on the contrary, they lead to deep senses, to radically different categories of archetypes.

We have tried to distinguish three great sides on which the paths of meaning activated by the landscape decline, through an interpretative model based on an antinomy: identity and otherness.

According to this criterion, our attention to the landscape normally goes in search of signs, distinguishing those that reassure us that we live in a known territory and those that arouse in us a sense of conquest, of expansion because we did not know them until a moment before and now that we have perceived them we feel we have enriched our heritage (of experience if nothing else, and sometimes of culture). On the one hand ‘the confirmation of identity through known signs, (on the other) the search for new trophies of signs in hitherto unexplored territories of otherness……But sometimes these two opposing tensions are not enough to explain the multipolarities of meaning that stir us when we look at a landscape: there is also their contradiction, the mad desire to dwell in the sacred, to experience a relationship with the environment without the mediation of domesticating apparatuses such as the sense of beauty, of order, and above all without the sense of meaning, trying to overcome the obsessive tension to semicity that reassures us and that is probably the intimate radical of dwelling: naming things, giving a reason for them. The panic sense, the romantic losing oneself, the belonging rather than possessing are products of a third drive, removed and repudiated by all gnoseology and almost all aesthetics, but which has certainly always agitated our culture and which persists, in the results of the artistic movements of the last three hundred years, on widespread taste’ (Castelnovi,1998).

Here is a first meaning of the sense of the sacred (in the landscape, but not only): a sense that, playing on its own limit (the sub-limen), allows us to grasp something, without going through the channel of habitual semiosis, perhaps using archaic mental instruments prior to the dominance of homo significans, as Eco defines it.

It is the discontinuity with the usual instruments of understanding that resembles that experience to the ‘sacred’, as it is defined in its first meaning in the best dictionaries; for example, the Treccani: ‘In the strict sense, that which is connected to the experience of a completely different reality, with respect to which man feels radically inferior, undergoing its action and remaining terrified and fascinated at the same time. In opposition to the profane, what is sacred is separate, it is other, just as both those who are assigned to establish a relationship with it and the places, destined for acts with which that relationship is established, are separate from the community. The sacred is that which men perceive as totally other and which manifests itself with mysterious force, with respect to which they feel subjected, frightened and at the same time attracted’.

In any case, the definition seems to refer to an event, to a manifestation, not to a stable configuration of things and of the soul that faces them: it is as if the sacred were in itself unbearable, not permanently bearable, to be taken in small doses because it is too different from man. If this temporal characteristic, of non-permanence, is also applied to space, we persuade ourselves that the sacred is not inhabited, does not take place in domestic places (or if it does, it transfigures them), the sacred space itself is a border space, a limen, a sort of outlook, from which for a moment fragments of another dimension are sometimes glimpsed, and which cannot easily be crossed back and forth.

Attention to the sacred in the landscape

But where is the space of the sacred in the landscape? Let us return to the general reasoning: albeit at the limit, however, as in every path of meaning, there must be a relationship between a subject who receives and a subject who produces. But the structural particularity of the sense of the sacred perhaps lies precisely in the different attitudes of the subjects.

On the one hand, the receiver: by now, not only every discipline of communication but also analytical psychology (from Jung to Galimberti) and even epistemology (Maturana) emphasise the need for an inner condition of availability for the channels of understanding to be open. Where this availability is lacking, communication does not take place. And this happens most of all in the landscape, where the communicative function is not relevant (i.e. little or nothing of the landscape has been made to communicate): therefore it takes willingness, attention, disposition to make sense of the landscape we perceive.

If it takes attention to attribute any meaning to the things we see, how much desire and attention will it take to grasp a sense of the sacred, a further, unknown sense, to which we are available? So on the side of the receiver, of the listener, there is a personal attitude, a predisposition to wait for the unexpected, as the Tao requires, a capacity to grasp ‘the sound of one hand clapping’, to perceive the Infinite and in that to be shipwrecked, that is, as Bachelard begins a splendid chapter of The Poetics of Space: ‘…it is an inner immensity that gives true meaning to certain expressions concerning the world that offers itself to our eyes… such immensity arises from a set of impressions truly independent of the information of the geographer’ (p. 207 )

On the other side of the receiver (because one is willing to receive) there is no intentional producer, as there is in ordinary communication. There is the landscape, the anonymous repository of every sign and also of everything that has not yet been perceived as a sign: what the Tao calls ‘the ten thousand things’, to mean a patchwork of elements that as a whole cannot be perceived as ordered by any law or structuring, until one is able to identify the Way, the one that gives sense to the whole.

But, outside of philosophical generality, the landscape presents itself in the form of places, different in themselves and differently perceived: we should have some competence in selecting the most suitable places for each type of experience. Here opens one of the pages most frequently visited by critics of modernity: we have lost all ability to perceive the differences of places. Just as entire disciplines studied where it was best to live, so every archaic culture identified sacred places, many of which have housed temples of the most diverse religions over the centuries, increasingly confirming the sacredness of the site. We do not: for the past couple of centuries, official culture has become scientified and has lost the sense of these ancient knowledges, much to the chagrin of scholars like Guenon, who laments the loss of traditional knowledge, of a sacred Geography (i.e. of the sacred) (as of a sacred History) i.e. centred on the places ‘. .most particularly suited to serve as support for the action of spiritual influences, and it is on this that the foundation of certain traditional centres has always been based…of which the oracles of antiquity and the places of pilgrimage provide the most outwardly conspicuous examples…’ (from Il regno della quantità e i segni dei tempi,Adelphi 1982 (1945),p.132.

We have lost this profound knowledge, but we can try to imagine its outcome, for those who possessed this ability. Certainly we could not assume where the sacred event (the voice, the burning bush, the apparition) in itself utopian is most likely to occur, i.e. anywhere. But with ancient wisdom, that which spoke amicably with God, it was certainly possible to recognise the places where attention towards the sacred is most easily activated, towards a capacity to begin a path of further sensitivity, an initiatory path, in fact.

It is this second dimension of the sacred that we seek in the landscape, if not a door directly open to the other from us, a system of traces, of presences that help us on a path that is certainly an interior one.

From the archaic (far away from us in time, antediluvian, or still present in time but far away in culture, anti-Western) surely the intuition still comes alive that we can search for places suitable for a sublime experience, as Kant defined it, or at least that facilitate the listening to a new sense of things: Elemire Zolla speaks of the Mountain (how can we forget Renee Daumal’s extraordinary Monte Analogo?), Simon Shama extends the field of investigation to the sacred stories of the Forest.

In a beautiful page, Sergio Quinzio compares the two archetypal places of the sacred, the forest and the desert: ‘For pagan, cosmic religions, the forest is the most evident manifestation of the pulsing of the divine forces that animate nature, and therefore the most intense sacred symbol… Opposite the sacredness of the forest, gloomy and full of the mysterious voices that the wind draws from the treetops, there is for the ancient monotheist the desert. Just see what the desert is for the Jew Edmond Jabes. The mystery does not lie in things, which are indeed offered to mankind, but beyond things, in the transcendence of the one God, of whom the boundless expanse of the desert is a symbol’ (in Boschi e foreste, ed.Gruppo Abele 1994, p.57). Luisa Bonesio takes the discourse further by exploring the differences of the three archetypal paths to a new meaning through places: the experience of the sacred in the desert, in the forest and on the mountain (in La terra invisibile, Marcos y Marcos,1993).

The space of the psychological sacred and the sociological sacred

To all of us, these ‘reconstructions’ of a past ability to establish relationships with the sacred through places give rise to a glimmer of awareness, we compare it with fragments of our own experiences, of desert, mountain or forest landscapes we have lived, and we realise that there really is a space to which we can reconnect, a polarity towards which we can reorient ourselves, but that the path is complicated by other experiences of the landscape, apparently close but giving rise to senses quite different from those of the archetypal sacred as it has been delineated so far.

The discourse becomes complex, intersecting general topics of evaluation of our time, of which there is a wealth of debate over the years in philosophy, anthropology and sociology. It cannot be condensed: we can refer to it by pointing out, for example, some of the perspectives to which we are led but which deflect us, seeking an experience of the sacred in the landscape:

a) in the first instance we are induced by the urban culture that has besieged us for at least 200 years, to confuse the search for the natural with the search for the supernatural. We cultivate an abstract idea of the natural, with which we now have direct relations that are as rare as with the supernatural: our constant attention to the signs of the landscape is confirmed in landscapes that are always rich in signs, in landscapes that are culturised in manufactured objects and not only in our gaze. Nature thus becomes, in our desire to encounter otherness, a phantom that is superimposed on the anxiety of the sacred, and the imagery that accompanies our personal, artisanal and vague sense of the sublime are increasingly linked to natural spaces that would probably have seemed normal (insofar as inhabitable) to the archaic wise, to experiences of contact with a nature that we transfigure while for them it is home (remember Dersu Uzala, the forest guide protagonist of Kurosawa’s masterpiece). But we have lost both familiarity and respect, that which makes the Seattle chief of the Apaches sing that everything is sacred, because the entire experience of life is in intense relationship with a nature that has its own autonomous system of signs and values, respected as different; our relationship with nature is mythical: Zolla says that we seek an astonishment but we no longer have the gaze capable of naivety;

b) in the second instance, we are induced by a millenary search for community to pay attention to its own cultural heritage, to the signs of itself that the koinè traces in places to hold its components together. We share anxieties about identity and seek confirmation from places, from the landscape: we seek homelands for our people. The landscape we have shaped is all a sign of our living, as a lineage, our best gazes look to that, our best cultures develop the best projects to enrich the heritage, our best policies defend its continuity. Last but not least, the European Landscape Convention, in which we place so much hope for a new valorisation of the landscape as a system of signs recognised as their own by the populations. But it is precisely this domination of the social, of the cultural, desired and well-liked (woe if it were not there), that makes us neglect the aspect of the personal, direct and unmediated adventure with the landscape, in search of that further meaning that is already difficult to achieve in a solitary experience and never in a group. The sense of the koine by definition cannot immerse itself in a foreign environment and remain steeped in it: it maintains an impermeability, it makes a shell of an environment known through its internal relationships and cannot access otherness. We all know that if one goes in a group abroad, one cannot learn foreign languages, let alone the experience of the sacred. Ulysses teaches us: he had to detach himself from his own to listen to the Sirens, even though his companions prevented him from turning the sublime experience into the ultimate journey;

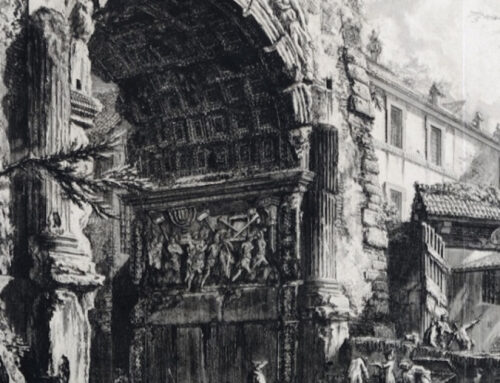

c) in the third instance, and in coherence with the choice to privilege community relations, a process of symbolisation of the sacred, of shifting from direct and ostensive experience, involving the senses and sense, to an abstract, representative, ritual communication, has been triggered for over a millennium. And in the West, this symbolic representation is based on building acts, signs in the landscape (this is not the case everywhere: think of the rituals of the Australian Aboriginal communities recounted by Chatwin in The Routes of Songs). In our history, on the other hand, we have the same sequence everywhere: first there was the sacred place, made sacred by the presence (or manifestation) of the God, devoid of human signs; then the community marked the sacred place with its own building, the temple, then the sign of the temple, which remained as a testimony to the ancient devotion to the sacred, detached itself from the place where the God is and was built where the devotees are. The temple now renews the relationship between the community and God, but prescinds from the place where this took place; it constitutes in itself a simulacrum of a sacred place, a symbol made by men for men that represents a seat of the relationship of men gathered in community with that which is other than man. Temples spread, they are no longer the signalling of a destination for pilgrimage to the sacred place (prior to the temple), they are a testimony to the widespread existence of communities that desire contact with the sacred, they are a sacred pret-a- porter, a service to the community. It is no coincidence that in civic administration, places of worship are considered services to the residence.

From discovery to the factory of the sacred

With these three delirious paths, that is, which leave the furrow of the original relationship with the sacred, the landscape as we know it is devoid of a consistent trace to find places where to have an experience of a sense of the sacred, while it is dense with symbols of the liturgical behaviour of the community. When, today, these human signs are acquired in our sense of the landscape as significant of sacredness, it is evident that we are faced with a third type of sense of the sacred, quite different from the first to which we have so far referred.

And the more the first sense, that of the living and direct relationship with otherness is elusive, unmarked, distant to the extent that we do not know the experience, and the more the second sense, which helps to find a way with effort and luck, requires a particular aptitude and stubbornness to allow an experience, the more on the contrary the third sense of the sacred finds easy satisfaction, in the evidence of the signs of the built, well related to the system of the testimonies of the history of the community, lived in daily behaviour, understood by all as a symbol of the community itself more than of its relationship with the sacred.

So with this passage we are at the factory of the sacred: we no longer have to find it, we produce it, or rather we produce its symbols. We architects have for thousands of years been in charge of producing places that reproduce the sense of the sacred. Indeed, architecture itself bases its noblest quest on the demand for the sacred of the communities it serves.

For the most part, it limits itself to attempting to reproduce the sense of the sacred in an interior, or at any rate in a confined space, whose every aspect is controlled, whose perspectives and entrances, horizon of gaze and effects of light are adjusted. The landscape remains external to the artistic work of reproducing the sacred. In the landscape, one signals that there is a reproduction of sacredness at that point. And to better signal this, sites of particular prominence are chosen, forms of particular difference for greater legibility, proportions of particular emergence.

And where this work lasts for centuries and occupies the best minds and energies, the landscape is repolarised, it rediscovers a network of reference points, not necessitated by the events of an uncontrollable and alien relationship with the sacred, but planned, integrated into the system of the signs of settlement, a not insignificant part of the heritage that is passed down through the generations: in the cultural landscape, the sense of the Sacred becomes the sense of History.

And the History is that of the settled community, which represents in the weave of the landscape shaped by its work the warp of the signs of its liturgy and devotion.

The search for the meaning of the sacred is thus separated from devotion. And this, in isolation, becomes a focus on the higher values of one’s personal and social life: it no longer has God in himself as a reference, but the testimony of other men, their martyrdom. The two desires were united in the practice of pilgrimage, which produced, among other things, knowledge of extraordinary landscapes, memories and cross-cultural images fertile for innovating stationary cultures that lacked an idea of the variety of the world. The search for the sacred was accompanied by the experience of man’s landscapes.

Today, the devotional one is only one of the thousands of tourisms into which we specialise our leisure time; for us, it is no longer the landscape of the journey that is important, but that of the destination. It is on the new destinations that we must focus our attention: devotion to the exceptional places of history leads to the sacralisation of the space of human events sublime for their horror, landscapes that one must experience because their meaning cannot be enclosed in an image, it is incomprehensible via television. Extraordinary in the overload of signs that surrounds us, they are unspeakable landscapes because sacredness manifests itself through the violence of empty space, the loss of signs: they are Auschwitz, they are Ground Zero.