Landscape to cope with global change

All the goodness of the earth

Cesare Pavese, in Feria d’Agosto (1946), has Sandiana say: ‘”everything that is born is made of earth; water and roots are in the earth; inside the grain you eat and the grape wine there is all the good of the earth. I had never thought that the earth served to make grain and to sustain us, all the more so now that I was studying.”

More than sixty years after that statement, in a hyper-urbanised world where agriculture occupies only a few percent of the population, there are certainly many more people who are completely unaware of what soil is, what it is for, how basic it is to our existence.

Even in Pavese’s time, the soil of a country was considered sacred: wars were waged for the soil, especially because it meant food and raw materials. Agrarian soil, where cereals and vegetables were cultivated, the basis of a people’s diet. Soil for growing fodder to feed livestock, not only for food but as a source of mechanical energy – oxen, horses, mules – and valuable materials, leather, hides, fat, horns. Soil to grow textile fibres, hemp, flax. Forest soil to provide timber for building and burning. Those who had land were rich, but with a richness made up of complex ecological and thermodynamic relationships, a source of moderate well-being as long as environmental constraints were respected: replenishment of organic matter, water regulation, irrigation, erosion control. A relationship honed over millennia of agriculture, which has passed on to subsequent generations a substratum that has even improved compared to the original conditions: levelling, levelling, drainage, fertilisation.

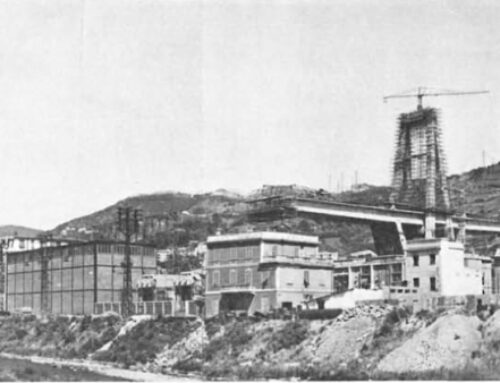

The Italian countryside, heavily occupied and cultivated since Roman times, nurtured around 80 generations of our predecessors and survived almost intact until the dawn of the industrial age. With the advent of fossil energy, the relationship between man and his land suddenly changed: no longer tied to a local source of energy and raw materials, easily obtained through imports from more propitious and cheaper locations, the guardian of the soil gradually turned into its predator. In the first half of the 20th century, there was only a modest urban expansion due to real demographic needs and rational industrialisation, generally located near mining and hydroelectric resources, rarely coinciding with districts of high soil quality. In the post-World War II period, the decoupling of industrial production from the territory reached its peak, with the massive occupation of flat land with high agricultural potential, close to major communication routes and therefore functional to the needs of trade and industry. In the early part of the year two thousand, we will finally witness the paroxysm of the speculative process, where the building of land will no longer respond to actual needs induced by industrial or commercial structures, but will be carried out a priori, aiming at the change in land value and the creation of demand for the use of spaces that are also not in demand. A predatory process no longer connected with a planning that can be defined as ’emergent property’ of the land, the result of the countless stratifications and interactions with the inhabitants and their personal histories, but rather generated by the mere and trivial temporary maximisation of profit. A few actors – construction companies, land owners and complacent public administrators – have proceeded to change the destination of land from agrarian to buildable in order to make a quick quid, heedless of any short- or long-term consequences on the environment, the landscape, and society. A few days of bulldozers and concrete mixers, and land that has been cultivated and cared for for thousands of years is suddenly destroyed and replaced with a construction project. And I emphasise destroyed, because a soil horizon useful for profitable agriculture is not formed overnight, but is a natural process mediated by the climate that takes millennia to evolve. Remaking soil after it has been removed is not possible, at least not in human times.

There are ‘artificial soil’ substitutes, but they cost energy and raw materials, and can only be applied on a small scale. In short, the destruction of soil by sealing and building construction is – on the scale of human times – an irreversible process. In this term lies all the importance and urgency of a problem that is now as disruptive as it is neglected: the senseless consumption of soil, and almost always, of the best soil. Soil is our insurance policy for the future: an aesthetic value for the landscape and a tourist attraction, certainly, but above all a guarantee of proximity food production even in times of energy shortages, an indispensable location for closing biogeochemical cycles, from the purification of civil and agricultural organic waste to the sequestration of CO2 to limit climate change, from filtering water for drinking water purposes to the containment of flooding events, from the production of vegetable raw materials to combustible biomass. If we want to save the precious soil that still remains, it is essential to change legislation quickly: from being a passive support to other, often ephemeral, economic activities, soil must become an economic entity in its own right, a producer of irreplaceable services recognised by the market economy. However, the latter has proven over the past fifty years to be insufficient to regulate the price of soil according to its scarcity: this is one of those cases of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ described by biologist Garrett Hardin, where by the time we realise the fault, it is too late to repair it. When we will need the soil again because the energy and climate crises will radically shift the economic flows of matter and energy, the price of the surviving soil will perhaps skyrocket, but it will do nothing to return the lost soil to the community. Here is a case where a wise public administration has a duty to make a corrective; it has a moral obligation to avoid the temporary maximisation of profit from squandering the limited and non-renewable common good ‘soil’. The first step to achieving this goal is numerical knowledge of the extent of the failure: how many hectares are sealed every day, every month, every year? And where? And in what class of use capacity?

Then urgent and radical regulatory action must be taken to discourage the continued consumption of better quality agricultural land. Protection based on the landscape criterion, which could have curbed certain excessively free uses of the land, has proved to be a failure: the superintendencies have often been very diligent in preventing the installation of a few solar panels on roofs, but they have been unable to do anything against the endless concrete spillage of warehouses, industrial-industrial zones, production settlement plans, commercial citadels and hypermarkets and outlets, which are still in place. Similarly, thousands of environmental councillors in regions, provinces and municipalities have put up very little opposition to their counterparts in the town planning, building and infrastructure departments, who have apparently always got their way with rebar and concrete mixers.

However, land consumption is a road with no return, and today’s mistakes will weigh on the generations of a very long tomorrow.

A few bibliographic suggestions for further study:

Mercalli L., Sasso C., 2004 – Cows do not eat cement. Ed. SMS

Rognini P., 2008 – Sight offended. Visual pollution and quality of life in Italy. Franco Angeli Ed.

Bevilacqua P., 2007 – The earth is finished. Laterza

Erbani F., 2003 – L’Italia maltrattata. Laterza

Luca Mercalli

climatologist, Piedmontese, president of the Italian Meteorological Society