Innovative enterprises are an economic entity that is emerging with a specific identity: a kind of fourth capitalism. They are ‘pocket-sized’ multinationals or territorial enterprises that have restructured production districts, built new supply chains, invented new forms of supplier relations, incorporated knowledge and research capabilities, and created garrisons in international markets in a wide variety of sectors, including especially innovative ones such as the green economy.

Innovative companies are not isolated: on average, they maintain relations with 240 suppliers, and are the strength of the ‘made in Italy’ brand.

However, is there a landscape of innovative enterprise?

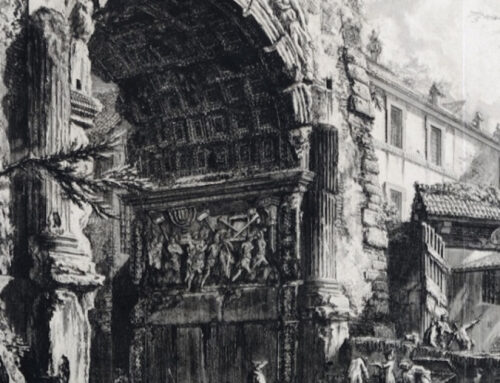

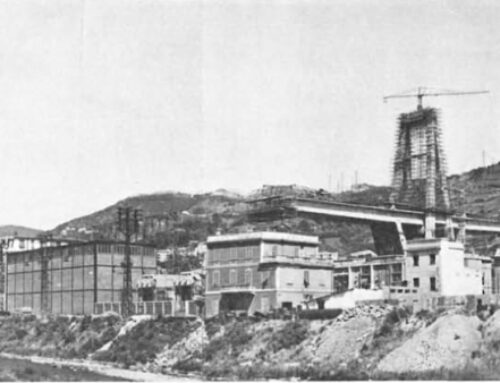

In the three previous phases of capitalism (the first of big business, the second of capital assisted by the public hand, associated with the establishment of the IRI, the third of small and medium enterprise, of molecular capitalism, of widespread industrialisation, of the urbanised countryside), enterprises expressed their own landscape-generating force, for better or worse. In the fourth capitalism, of innovative enterprises, this transformative drive is not very visible.

The landscape of new enterprises is mostly an internal landscape, innovation is all internal to markets, to the supply chain and does not reverberate in the territory.

In the last 10-15 years, the innovative company has been confronted from within, by necessity, with the environmental issue (with the green economy, with quality certifications), which has entered directly into the company’s income, because better control of production processes leads to higher quality production, which in turn determines an increase in exports and thus an increase in turnover. Conversely, the quality of the territory and landscape, companies have not incorporated it, because they are not required to have the territorial quality stamp, which is perhaps taken for granted.

Paradoxically, in the 10 years during which fourth-capitalist companies have established themselves, constituting the benchmark for the environmental quality of production processes, there has been, in parallel, the greatest consumption of land and land degradation.

Many territories that currently enjoy a positive image from the point of view of the landscape-environmental and territorial resources at their disposal, may not be able to maintain it in the near future.

Some questions arise spontaneously: do innovative companies perceive a sense of landscape? Are they aware that landscape is a common good? Can landscape and territorial quality be an aggregating objective for fourth capitalist enterprises?

These companies are well aware of the evocative power of landscape, as the success of visitors to the Italian pavilion at the Shanghai Expo testifies.

The Marche Region, which is the most export-oriented manufacturing region in Italy, in percentage terms, presented itself at the expo with a film in which the representation of the landscape was traditional, based on historical territories and characters, Recanati and Leopardi, Pesaro and Rossini, Urbino and Raphael. If, on the other hand, the Marche region had presented some images of the new architecture commissioned by manufacturing companies, thus symbolising the landscape produced by fourth capitalism, it would not have been equally successful with visitors, because it would have automatically been stripped of its evocative power.

The companies that are members of Symbola consider territorial rootedness and anchoring to the local to be fundamental elements, also in the internationalisation processes. The foreign representative or buyer who once came to Italy to conclude negotiations was taken to the nightclub, whereas today he is taken to visit the castles, villages and art galleries that dot the whole of Italy, he is accommodated in hotels in the historic centre, he is taken to eat in the best restaurants and the best wine cellars; this is the meaning of the landscape.

Landscape is also mutual loyalty between companies and workers, the awareness of having a human capital of excellence, the personal and territorial pride of ‘doing one’s job well’. It is a principle of identity, it is the pride of tradition, both when one is its heir and when one is its initiator. Entrepreneurial adventures are individual life projects but at the same time community and territorial experiences.

In relation to landscape capital, it is interesting to note how forms of sponsorship have changed over time, from financing the local team to financing the recovery and restoration of degraded historical assets.

However, we do not consider the present of our landscapes (including the landscape of fourth capitalism companies) worthy of the contemporary, let alone our past; it is as if we do not want to see everything that erodes and degrades the Italian landscape, what we consider repulsive, despite the fact that we are responsible for producing such degradation.

The owners of the innovative companies, the neo-bourgeois (those who have stayed in Italy, who have developed a social and corporate responsibility, who have latched on to supply chains, who have invested locally, who are environmentally virtuous) do not want to be represented by the territory in which they are located and which they help to develop. It is a process of removal that contradicts other territorial investment capacities: on social, environmental, entrepreneurial capital.

It is therefore becoming increasingly important to make landscape and territorial quality part of business strategy, as is partly happening in the agri-food sector.

It is necessary to identify the picks to open this broken connection.

One theme around which innovation companies can coalesce, with respect to the territory and landscape in which they are located, is security.

Although it is difficult to foresee a radical turnaround, entrepreneurs are realising that if the territory is eroded and degraded, they will lose its embedded evocative capacity.

But the main strategic element around which to build a shared strategy is the pleasure and pride of living in an area endowed with a highly valuable territorial, social, landscape and environmental capital. Entrepreneurs must be called upon to take responsibility, as territorial leaders, to prevent this capital from being dispersed or destroyed.

This responsibility must also be shared by politicians, so that they do not bow to the conditioning of local elites, who are all too often not very strategic and only tied to short-term property income, but know how to make a pact between all stakeholders, creating a network and a shared vision of the Italy of quality.

Fabio Renzi

from the Marche region, Secretary General of the Symbola Foundation for Italian Quality