A topic of particular interest today is the relationship established in recent years between banking foundations and the landscape. Foundations are not functional parts of their generating entity, the banks, but are conversely independent from them; they are subjects of social freedoms, according to the definition given by the Constitutional Court, residing in the territory, endowed with important assets and whose ultimate goal is to help the territory in which they are located to develop.

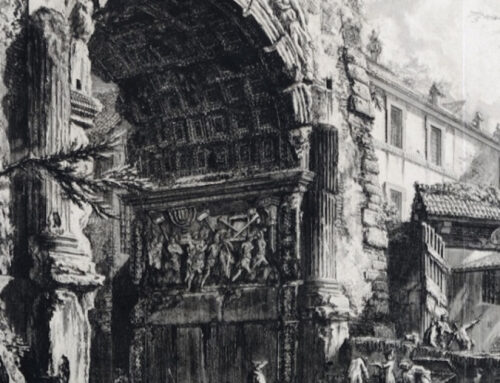

Most foundations have focused on projects for the recovery of historical-artistic heritage, which is widespread in Italy and constitutes an immense patrimony that, however, the scarcity of resources is slowly consigning to a state of degradation and abandonment.

In recent years, Italian banking foundations have guaranteed an average allocation of 400 million euro per year to restore these assets, particularly those located in rural areas, but also involving assets located in large cities.

It is also the task of foundations to support in the third sector all activities that intervene, either in itinere or a posteriori, to improve the community’s enjoyment of assets with historical-artistic value, whether they are the result of man’s flair and skill or the fruit of nature’s incessant work.

These assets, in a long-term planning perspective, can become extraordinary economic factors of the territory.

Since 2011, the foundations, which do not have an electoral periodicity can initiate long-term strategies, have undertaken to implement 10 experiments throughout Italy (for Piedmont, the cities of Fossano and Biella will be involved), with the aim of calling together the intelligences present in the territory, currently relegated to the private sphere and rarely involved in public affairs.

The intention is to exploit the third party position with respect to private individuals and politics and the authoritativeness of foundations to collaborate with the public administration in order to gather intelligences to think about the identity of their territory: if there is one, if it has been lost, if there is one to be discovered. One would like to use the financial resources made available to force public administrations to invest in long-term projects. The ‘cathedral-cities’ project promoted by the CRT foundation and the project developed along the Stura, from Cuneo to Cherasco, to make the routes, which have slowly become inaccessible, usable.

Another problematic situation the foundations are working on is the lack of social cohesion within local communities in southern Italy.

The family, under certain conditions, runs the risk of being an institution closed to the outside world, which prevents the development of horizontal relationships between the different nuclei. The Foundation’s objective is therefore to recreate a social infrastructure in southern Italy, promoting associative forces among citizens, especially in the most deprived neighbourhoods, stimulating social cohesion through the creation of animation nuclei, intervening especially in small rural and suburban realities in large cities.

The Foundations are also developing social housing projects, initially conceived and promoted by the CARIPLO Milan Foundation, but which are slowly multiplying in terms of the number of experiments financed: these are investments aimed at tackling at least part of the housing problem of the ‘middle’ segment of the population.

The target group in this case are citizens who are rich enough not to be able to compete for social housing, but conversely too poor to access rents or to become owners of market-rate housing.

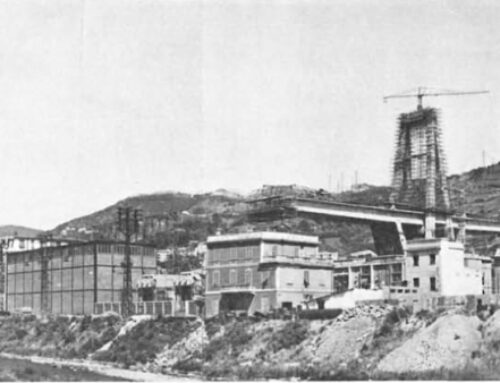

Municipalities, however, when building new housing, always build ex novo in the expansion areas envisaged in the master plans, as the restoration and reuse of disused, unused, empty buildings represents a higher cost from a strictly financial point of view.

This issue is clearly in conflict with the now alarming and extraordinarily topical issue of land consumption; it is a problem that must be tackled as a matter of priority at the cultural level, before being addressed at the regulatory and management level.

The case of the city of L’Aquila is emblematic: a ville nouvelle has sprung up around the city destroyed by the earthquake, while the historic centre remains in a state of decay and neglect.

Beyond the problem of lost land, already a serious matter in itself, there is a social problem linked to the obvious difficulty of repopulating the historic city, which thus slowly becomes a modern-day Pompeii. These are also very topical and substantial issues that could find a way forward, a less contradictory solution, if the sense of identity and the local landscape were taken into account.

Antonio Miglio

agronomist, Piedmontese, President of the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Fossano, Vice-President ACRI Associazione di Fondazioni e di Casse di Risparmio spa