Seventy years of sudden and overbearing urban development have generated the generalised trivialisation of spaces, the loss of identity of the suburbs (which now go as far as the thresholds of the historic centres), and even the latest initiatives aimed at renovating obsolete and degraded parts of the existing city show an inability to redevelop and above all to make sense of the urban form.

Until now, the development of the city has been dealt with, with varying fortunes, by town planning. In the last century, this technique, which is always in danger of appearing to be a cousin of architecture, has kept the theme of the form and appearance of the city in a secondary role, privileging the functionality of equipment and the management of legal relations between territory and public and private intervention. Today, seventy years of sudden and overbearing urban development have generated the generalised trivialisation of spaces, the loss of identity of the suburbs (which by now go as far as the threshold of the historic centres), and even the latest initiatives aimed at renovating obsolete and degraded parts of the existing city show an inability to redevelop and above all to make sense of urban form.

Until now, the development of the city has been dealt with, with mixed fortunes, by town planning. But modern town planning is a technique born a bastard, with no origins of its own, from the Enlightenment and positivist engineers and physicians who found room in the courts of princes or the leaders of the young democracies, heir to a long history of utopias and colonial enterprises. In the last century, this technique, which always runs the risk of appearing to be a cousin of architecture, just because it is taught in the same degree courses, has instead kept the theme of the form and appearance of the city in a secondary role (unlike what is done in architecture for the form of buildings), privileging the functionality of equipment and the management of legal relations between territory and public and private intervention.

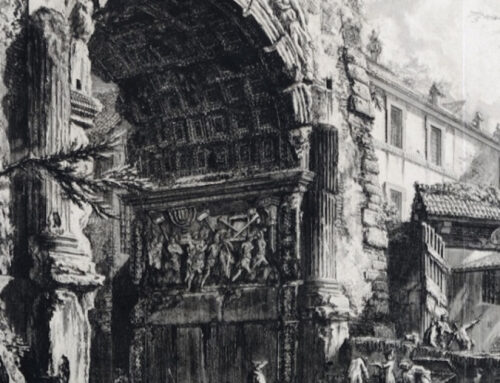

And one can understand why: the urban form of the city, from its origins up to the beginning of the 20th century, was mostly generated by spontaneous growth, entrusted to a few unwritten rules of an ‘implicit project’, sunk into everyone’s current culture: citizens and builders belonged to the same culture when they were not even the same people. When, from the mid-19th century onwards, a problem of representation emerged in the appearance of the city’s main public places, the calling card of the rampant bourgeoisie, the theme of form was often resolved with norms and techniques for controlling façades and monumental parts, with the Ornate Commissions or with regulatory profiles, postponing the theme from the city to the architecture.

Today, seventy years of sudden and overbearing urban development have generated the generalised trivialisation of spaces, the loss of identity of the suburbs (which now go as far as the thresholds of the historic centres), and even the latest initiatives aimed at the renewal of obsolete and degraded parts of the existing city show an inability to redevelop and above all to make sense of the urban form. While the functional aspects have the opportunity for interesting experimentation in these redevelopment programmes, the aspects of renewing the formal quality of cities are practically neglected, and all this reveals a serious cultural backwardness of the techniques and powers that manage the territory with respect to the needs of citizens, and above all it highlights a waste of opportunities, which will be increasingly rare, to give shape, identity, and polarisation back to the city.

Faced with the emergence of an issue that has become a burning issue due to the cultural backwardness of the techniques and policies that should administer it and the lack of consolidated tools to manage it, it is spontaneous to turn to other disciplines, different from that urban planning that has supported us up to now but that today is not able to give indications for the quality of urban form. These are disciplines that have developed in other fields and that can help us, thus realising an intercultural work: for example, those of landscape analysis and evaluation, of which here we try to give some indications.

Thinking about it, it is already an indication of contradiction that there is a disciplinary difference between those who speak of urban space and those who speak of landscape: it is as if ‘space’ for urban planners were a term that somehow belongs to the sphere of functions, while ‘landscape’ would be relegated to the sphere of sensations, of perception.

In fact, if the theme of these days is the urban system, we must always bear in mind that our judgement, as citizens who live in and enjoy the city, is largely influenced by what we perceive of the system, i.e. the urban landscape. The problems of managing form, identity, the effect on behaviour, and the symbolic role that space plays in the societies that inhabit and enjoy it have strong repercussions today on the sense of belonging of the new generations, on safety, and on the city’s capacity for use. This is why we feel it is appropriate to talk about the landscape, focusing on problems related to signs, aesthetics, and models of use rather than functional practices.

Precisely these are the specific themes of the renewed interest in landscape, which starting from the extreme peripheries of the territory, from the wilderness and nature lands, gradually invades settled territories (the ‘cultural’ landscapes) and a series of aspects of the city that we have hitherto neglected because they seemed superstructural and that now become the first problem.

The fact that landscape issues have developed somewhat separately from urban planning issues can be helpful at this point in time: we can try to evaluate their contents and methodologies as a source of potential innovation to address an issue that, with the ‘traditional’ instrumentation, does not find solutions.

So we set out to examine certain categories of landscape investigation and study, apply them to the city, and test whether public space is approached with these categories; then we assess whether public space can be described, evaluated and then designed as an urban landscape.

Landscape is a factor of meaning. It is not the object ‘world’, but the way the object ‘world’ is received within us. Landscape is an investigation of an interaction: that between the user and the outside world.

For example, we are interested in studying what motivates the tourist’s gaze, why tourists visit historic centres, what is not only the motivating element but also the reasoning behind it. Or we are interested in the attitude that makes the inhabitant tied to his roots, the reading of the landscape by what is called the insider; or what generates a feeling of discomfort or even a sense of offence when we are faced with an impacting element, as if we had a ‘common sense of landscape’, when we are uncomfortable in the face of a transformation, of violence against an established landscape.

This interaction is based on perception, fruition and the only partly rational processes behind the sensations and memories that are deposited by the sensations. A complex world is involved, the one that involves the management of our personal and collective cultural sediment; to realise the practically infinite connections of this reference, it is enough to think that the entire psychoanalysis is founded on the world of sedimentations that events generate on our personality and culture. To delve into the meaning of landscape, we must address this worldview, at least for the aspects that most directly involve the perceptive relationship with the external environment and the ways in which the memory of places generates values, affections, motives for design choices or life.

Let us try to understand how we distinguish, in the continuum of perception of our surroundings, those elements and relationships that settle as accomplished and distinct from others, as we move through space and perceive them as part of a whole. In fact, our perception of the landscape, outside of closed environments, is not linked to precise spatial units, unless in very particular sites. Public space is made up of interconnected spaces, it is a system and when we appreciate a landscape we always appreciate it as a sense generated by a system of spaces.

So, first of all, we need to understand how the sense of a place is generated within us from a system of sensations relating to individual spatially and geometrically defined elements, which is accompanied sooner or later, strong or faintly, by a general, overall sense effect, linked to synthetic and holistic aspects, which cannot be broken down into simple elements.

This is a passage of great complexity, in the face of which the scientific side of landscape analysis cedes its arms to the artistic side, to painting or literature, to photography or simply to the taste for places that each of us retains in our memory.

Technically speaking, if in order to study landscape we must understand the way in which the relationship of fruition takes place between the world to be perceived and those who perceive it, it is appropriate to have recourse to the methodologies of a discipline that has approached the subject in structural terms: for example, semiology, which is that discipline that studies communicative relationships on the basis of signs, of relationships established in various languages between physical elements (such as sounds, graphics, movements or objects) and pre-constituted meanings that have been connected to those elements. In semiology But in language – and semiology relies completely on it – at the basis of communicative experiences we have a vectoriality, a unidirectionality of the text (time in verbal discourse or alignment on the line in writing) that pre-constitutes for us a specific order through which we reconstruct the rules of the message, but in space this vectorial sequence that helps us understand the rules is much more complex, because in practice it depends on the ‘looking’ (or rather ‘sentient’) subject to establish what the order of perception of things is.

If each person were to tell his or her own landscape ‘units’ (as if they were sentences in a speech), even if we were facing the same territory, we would have very different narratives. Moreover, most of the urban landscapes we experience are very messy and complex, and the issue of the different consideration of landscape partitions is a first problem that emerges strongly in its operational implications: for the architect, for example, when he finds the difference between the spatial consideration of the geometric units of his project (i.e. how he imagined people would perceive those places) and the urban landscape as it is actually perceived and experienced (it would be better to say in the plural: … the landscapes…).

A first step in the necessary ‘humility’ of the designer lies precisely in being aware of the difference between the designed object and the whole perceived by the user as a landscape, in which the designed object is inserted within a much more complex spatial system than expected. In short, we verify each time that the object or space that we have designed tends to become one element among many, even to the point of dissolving into the system of landscape relations of that place, relations that everyone sediments in their memory into a single whole, into a holistic image.

In short, ‘our’ public places (such as the new squares we have designed, such as those that we protect as historical heritage, such as those on which administrations invest tens of billions in paving and furnishings) are only very rarely a ‘destination’ for the user of the urban landscape, which gives meaning to a much more complex effect, sedimented in entire itineraries through the city, in networks of different and distant signs that compose in the memory an overall effect of meaning, difficult to dissolve in the individual episodes that compose it.

Given this relative naivety and the widespread inability to understand the behaviour of the main interlocutor of our projects, that “public” to which the space of the same name is dedicated, we need to understand how we distinguish in the continuum of perception the elements that make up the image of the landscape that is consolidated in memory, the one we can talk about, that enters our cultural and sentimental heritage. If it cannot be interpreted as an articulated sign system, to which model can we refer: to a structure of symbols with strong references to already sedimented concepts? To a holistic synthesis that we absorb with sensitive and uncoded capillaries?

When we design, we strive to refer to the effects that our space will have on memory, on cultural sedimentation, on the sense of identity, and we can hypothesise that this sedimentation process is structured through symbols, as we think happens in the case of large monumental spaces, which signal a ‘strong’ sense in the user. But we know that in fact, living in an urban space, the image of the city is not only made up of monuments and places that stereotype the sense, that the urban landscape is not only given by postcard images, but that rather the sensation of the city is given by the feeling of relationships of minor elements, not very significant one by one, but organically connected in our perception.

This is why the symbol structure is not a sufficient interpretative model, nor a sign system articulated enough to describe urban space. With this model, only certain elements are described, but the part that is most interesting for evaluations and choices, the part that generates feelings of pleasantness or discomfort, escapes the model made of signs referring to precise concepts.

We must leave interpretation to the endogenous and personal capacity for holistic synthesis that relies on a union between sensations and rational elements, and thus on the understanding of rules and values linked to direct perceptual verification.

All this has been studied in the analysis of the landscape in the more or less romantic sense of the term, i.e. in the fruition of open, natural spaces, and only recently in the fruition of places settled by the so-called ‘cultural’ landscape. Certainly we can import these early critical approaches as useful criteria for the study of the city, in dialectic with the regulatory criterion of those who think that the city is an ordered system of artificial productions.

But our way of perceiving the world, and therefore also the city, is so mixed with sentimental and rational elements, that even trying to order everything we can only use our own subjectivity, especially taking into account that part of the sensation is also due to the perception of elements of the physical context that have not been designed. An example of this complexity is given by the best architectural photographers. Basilico takes pleasure in photographing the ordered city that deviates, that has points of slippage, that becomes interesting because it has elements that, due to historical sedimentation, random events, or because a particular space has really been configured, is not the one that would have been envisaged, that had been designed, above all it is not the one in the model we had in our heads when we started to walk around the city. In his photographs, Fontana presents us with unprecedented, unforeseen geometries, ordered landscapes that lie between the lines of the (much less perceived) designed orders, but which are ‘other’, which emerge in an unforeseen and ‘revolutionary’ way to the curious gaze.

It is evident, starting from these assumptions, that what we are most interested in are the stimulating properties of the landscape, disturbing those who seek certainty with scientific categories or order with design techniques, those that compel an exploration in complexity, an understanding in polysemy, a non-possessive and non-imperative design activity.

So here we do not seek to define the landscape as the object of our investigations and actions, but rather outline its potential as an agent provocateur that induces reflections in those who observe it, or rather listen to it, enjoy its feeling.

In this direction we discover new directions for a more general research, working on the edges of scientific knowledge and rational design, which begins to orient itself in an enormous, little-explored reservoir of potential: that which motivates the desire, the imaginary, the memory of our inhabiting the city and the world.

So, when we become accustomed to examining the ways in which we deal with the urban landscape, we pay attention above all to serendipity, that attitude that consists, to quote Zen, in ‘waiting for the unexpected’. Serendipity is a neologism that derives from a city imagined in the mid-18th century by Walpole, in which things are found that are not sought (and those sought are not found), in which unexpected events occur, in which the protagonists unexpectedly find the resolution to problems but in an unpredictable way. This term was coined to give an adjective, a quality to the places, the attitudes in which the unexpected is really most likely to happen.

This characterisation of the city, now proposed by more than one scholar (e.g. in Italy, Bagnasco), is not only a cultural provocation, but is taking shape as an area to be worked on in a disciplined and technical manner, and here too we would like to use it as a cognitive tool in the hands of planners and urbanists.

A second strand of important contributions to our approach lies in the recent exploitation of the action perspective on ‘cultural landscapes‘, reopened with the Council of Europe resolution (No. 53 of 1997), which defines landscape as “a determined portion of territory as perceived by man, the appearance of which results from the action of human and natural factors and their interrelationships“, and which applies to this landscape the commitment to “legally consecrate it as a common good, a foundation of the cultural and local identity of populations, an essential component of the quality of life and an expression of the richness and diversity of the cultural, ecological, social and economic heritage“.

This sensitivity of the Council of Europe, and for some time now also of the Italian government, applies to a society in which mobility has grown exponentially linked, not only to occasional movements, but linked to the fact that very few of us live where our parents were born, and that our children will live in different cities. It is the mobility of living that grows exponentially. The expanded accessibility of the circulation of images, not just people and wealth has led to an enormous complexity of our cultural heritage and this has led to a much more complex sense of dwelling than before, where dwelling and a sense of local identity were overlapping. Now identity is a much more articulated feeling: it is made up of different cultural references, of knowing networks of places, of feeling a bit more like an inhabitant of the world.

Thus, there is a weakening of the sense of local identity that must be somehow enhanced. No one was concerned about identity in any Italian city 50 years ago, because there was such a strong overlap between local identity and the inhabitants’ pattern of life and values that institutional protection of their identity was unnecessary.

Today, even though mayors claim autonomy in their urban development plans, wanting to give themselves the face of the city, and manage public spaces, because this belongs to them first and foremost, in reality they verify every day how much urban space (and first and foremost public space) is representing local society less and less, is felt less and less as an image guarantor of its values.

The power of anyone to identify themselves with networks of points in the territory is growing, but the power to manage, for individual localities, local identity, which is one of the basic values for any criterion of landscape protection, as it guarantees diversity and recognisability, is decreasing. The natural vestal of the different localities, i.e. the society that inhabits it, is being lost, the element that has been relied upon ever since the municipalities, on which the definition of public space was founded, are losing their socially inherent meaning. It is becoming more and more complicated to rely on a community and its representatives to make sure that we value places. We have to enhance places, but we have less and less the established historical subject that spontaneously takes charge of enhancing them.

In fact, the growth of mobility and our well-being diminishes our connection to local identity and increases our identity as tourists. Cultural tourism, the desire to recognise oneself through dialectics with other places that are not one’s own, but can become so, is growing. In this perspective, the tourist is no longer only an intrinsically destructive and consumerist subject, he can also be identified as a proponent of values. In fact, tourists are the environmentalists, the lovers of historic centres, the rediscoverers of ancient or industrial archaeology, the very members of the Council of Europe who voted for that resolution. Paradoxically, the cultural urges to respect cultural landscapes, in the Council of Europe’s proper sense, come in many situations more from the tourist than from the inhabitant.

So one of the issues we must ask ourselves is: which public space for the reunion of the inhabitant with the tourist?; that is, which urban landscape once again produces the extraordinary effects of Mediterranean centres, historical places of local identity to the point of being attractive to the foreigner?

The ‘public’ space comes into being in order to represent something, as well as to perform functions: in theocratic or regal societies it is the space of ritual, in mercantile societies it is the space of encounter and business management (the caravanserais, the markets), in the first democratically organised societies it is the institutional space (the forum, the arenarium) and the space of debate and teaching (the academy). In more recent bourgeois societies (of which the modern ones are all expressions), the space of all the previous representations becomes public, together with the social part of the private representations: in short, the representative force of the modern public space goes beyond the narrow circle of deputed places and pervades the whole city: every street, every square, every garden belongs to everyone because everyone is ‘democratically’ represented in them, in them they mirror their most representative behaviour. Hence the strength of the identity of the modern city with its people: space no longer represents something else (it is no longer a ‘sign’ in the sense of standing in the place of something absent), but represents the community itself that inhabits it, each citizen is both actor and spectator of the representation that takes place in public space. Therefore, each person feels somehow in need of finding his or her identity outside the front door, through the facade of the house. It is a problem of diffusion of the element of quality of life given by representing oneself.

We bring the values of the public space to our doorstep, we somehow interact in our private with the public space. So the need for identity, for the enhancement of the cultural landscape that we spoke of earlier, we find diffused reticularly in the city. It is a fractal proliferation of the sense of public space: the need for representativeness, the sense of local identity, the formation of places in which to find oneself.

This has two effects:

– Modern public space is everything in the city that is immediately offered for use, everything that has continuity, that cannot be relegated to individual places;

– modern public space is not aesthetically producible or manageable without the contribution of private actions.

We have to interact with the need for representativeness, for making sense of the micro-local identity of each area of the city. The local government must set the rules for the public aspect of the city and delegate the production of this public aspect in part to the relationship with private parties. Hence the responsibility for the new urban planning discipline to organise this relationship between public and private in function of those aspects of the urban landscape discussed above.

Historically, the bourgeois society that spread the sense of public space, regulated it to represent a precise sense of order and positive participation in a normalised system, for example in the 19th century with the Ornate Commissions.

Today, with the ideology of bourgeois identity, of being proud citizens of one’s city, gone, one no longer knows what to represent through public space.

The Rules

The relationship between the citizen and the built city is an iceberg of ideologies, patterns of behaviour and collective feelings that emerges at times in our daily lives, imposing at those moments a focus on processes and values that are always present but are normally latent, implicit, at the margins of our thoughts.

One of the moments when we realise the complexity of the relationship between our daily lives and the built city is when we measure ourselves against the rules that regulate the construction of the city. It is a mostly unpleasant relationship, one that is often dismissed as an empire of bureaucracy, a hated way of ‘laces and ties’ that prevent the spontaneous expansion of free personal activities.

On the other hand, however, there is widespread malaise about living in the newly built parts of the city, mobility towards the central and older areas, and a sense of powerlessness and disgust in relation to the newly formed public spaces, which are mostly uninhabitable, unsafe, and in any case unattractive.

Every now and then we meet, for the most diverse reasons, a technician in the field, and his frequentation makes us realise that the problem seems to lie not in the lack of plans but in the rules, that the city is not made on the basis of plans but on the basis of rules. And if the result is clearly unsatisfactory, one must first look at the rules that generated it. Or rather, perhaps we must look at the relationship with the rules, because we never know whether the rules are there but are wrong, or whether they are right but we do not know them, whether we know them but do not want them, whether we want them but are not capable of them….

In any case, we understand that the subject at stake is an inclusive, undifferentiated WE, that one cannot refer the problem only to technicians or bureaucrats, but that one must nevertheless attempt to read the roots of this contradiction in widespread sentiments in the background of the entire user community, in the ‘cultural properties’ that structurally connect citizens to the city.

It seems to me very interesting to try to tackle the problem ab imis, starting from its most general and finally political aspect: how much and how much the citizens care about the quality of the city (here of course we are talking about the ‘representative’ or ‘signifying’ part of urban architecture and therefore how much and how the rules for building (or enhancing) it are politically legitimised.

I will immediately give my interpretation of the situation with regard to the main question: in my opinion we (all citizens) want rules but (we technicians) are not capable of them.

Even in the nausea of overproduction of rules, in our case there are clear reasons for wanting rules:

* it is clear that a crisis of local identity is precipitating, which has been, at least in the Latin-Mediterranean area, a structural element of the city culture on which we have relied for the last millennium. Without going into the merits of the reasons for this crisis, we can pose it as the driving force behind an increasingly pressing demand for a new representativeness of the city, which is no longer automatically suited to the status of its citizens, for which the added values of trade and industry are no longer invested, which no longer bears witness to the ambitions of its inhabitants. With the vital automatism having lapsed, demand turns to institutions, assistance is sought for anaemic identities, plans are required to defend against the mediocrity and opacity of the urban image as against the progress of a landslide or erosion system: it becomes a civil protection problem….

* a historical aporia is evident in the relationship between builders and inhabitants, who are no longer part of a single cultural universe, they have become anonymous and incommunicative subjects, and this prevents a spontaneous and natural resolution of the problem, as it has always been addressed and resolved ‘in’ civil culture without the need to resort to the ‘thirdness’ of an external norm. It has now seized the mechanism of the service that the engineers did so well in the last century, of giving a recognisable and sustainable face to the city, which by now structurally was suffering the fracture between builders and inhabitants. Hence the shift in the dialectic between the consolidated image of the city and its evolution into a new form of political fiction, the “eidola aedilis”, the nefarious rise in importance of the “architects’ parties”, who fight among themselves, on the one hand in the role of official guardians of a cumbersome and malfunctioning system of constraints, and on the other in the role of provocateurs of formal novelties in buildings to distinguish the various clients. Under these conditions, the civil demand for a recognisable city that represents its inhabitants falls on deaf ears, replaced by the petty sectoral clamour of the debate on good or bad architecture….

* the degradation in the design of the city produced by the prevalence of the dialectic between private interests over a convergence on public interests is evident: the need for rules has recently been fuelled almost solely by the need to restore balances altered by private pressure.

In this situation, the classical reference, according to which the rules for building the city (few and definitely followed by actions) served the city itself to take care of its own image, while the rest was entrusted to a ‘know how’, evolving so slowly that it always appeared as consolidated knowledge, was lost. It seemed in the last fifty years that values such as the ‘equity of rents between owners’, the ‘homogeneity of fiscal and bureaucratic treatment’, the ‘willingness to transform each lot according to market opportunities’, were more important than values such as the recognisability of the different urban sites, the quality of image and self-representation of public spaces, the organicity of the residential system, from the most intimate room of the house to the urban centre.

In short, we have become so clogged up with rules dedicated to private relationships that we can no longer afford them, and we increasingly feel the absence of those elementary practices of regulating public affairs as an investment and day-to-day management, which were the basis of the city’s culture.

On the other hand, it means something that the city’s governing body, the municipality, is still one of the few vital institutions with the legitimacy in the general opinion to lay down rules, but on what is common (words make sense!)….

Second part of the statement: we, as technicians, are not capable of trying out these new (?) rules. Those who work in this field well know the sense of inadequacy that can be tasted both when trying to write into building regulations the conditions for obtaining an urbanistic outcome that one would like to fit in with the strategies of the Plan, and when trying to design according to quality criteria by zigzagging in the grid of constraints and indications that the regulations impose, and when evaluating a project in the light of the regulations.

In my opinion, the uneasiness stems from knowing that there is no specific enemy (with notable exceptions of bureaucratic monsters), but that the impotence sinks in something implicit in our culture, which has removed and denied for at least two or three generations not only practical but above all epistemological problems of great complexity, accumulating disciplinary and sectoral approaches in the ‘modern’ management of the city, antinomian to those that now emerge as necessary.

It is enough to mention some of the most pervasive nodes in the cultural context that binds us and holds us back from experimenting with new forms of regulation:

* we move from a technical culture of analysis and design all tied to ‘composition’, to the ‘assembly’ of parts, to elementary parametrisation, to mistaking the objectivity of references for objectivity of knowledge. It is clear that with these foundations we find ourselves inadequate in the face of a real epistemological problem: to distinguish within a field that is not very discreet, in time and space, such as that which derives from the feelings of living, which we are accustomed to perceiving in a holistic way, which gives rise to absolute evaluations such as “it is beautiful”, “I feel good in it”, “I feel at home in it” (or, more often, their opposite).

On the contrary, technical normative traditions follow from the Enlightenment assumption of the intelligence of phenomena through the anatomy of their parts, of the simplification of relations in functional and causal terms, of the denial of the drifts and complexities that arise in the processes of realisation and permanence: things in the city ‘are’ once and for all and the norm intervenes in their abstract constitutive moment, determining the individual elements that constitute them.

Until now, we have not been able to break the taboo, to overcome the obligatory “objective”, analytical reference of the norm, and we reduce ourselves to this single regulatory modality even when it is clearly counterproductive: we produce mostly parametric indications on individual elements, in the face of a complex regulatory objective that is unavailable to simplification such as architectural quality, or the quality of the sense of living (even more difficult but more interesting for the ethos of regulatory action).

* the normative tradition based on the object prescription is combined with other aspects of the dominant culture, causing other more specific barrier situations for a reasoning on the quality of living:

– we become accustomed to never evaluating space, but only the elements that surround it, and this ‘deviation’ of the centre of attention is not challenged even by the recognised quality production of the masters of modern architecture, who increasingly tend to produce objects, volumes, and not spaces. So, while on the one hand the feeling of urban quality is certainly aroused by “being in. ” and not by “looking at the….” and the judgement of quality of living moves from the complex of signals that we read through the spatial perception of the environment, on the other hand we have not only explicit norms, but models, authoritative examples (and therefore implicit rules of the architectural super-ego) that do not deal with the space in which we live but with the “aesthetic quality” of the built objects. It is clear that in this situation the gap between “common sentiment”, common sense that combines the appearance of the city with the activities that take place in it, and the “sense of architecture” of the technicians and insiders is split right from the primary references: different languages are spoken, but above all the “texts” on which the discussion is based are different. Hence the risk that, even with good will, yet another proposal for “internal” regulation will emerge from the technicians, regulating, according to any inductive method with respect to models, the qualities of the construction of buildings, without any correspondence with the real demand that instead orients its evaluations on the complex spaces (and almost never designed) in which one recognises oneself as a citizen;

– technicians become accustomed to not considering the continuity of public space, which is instead the true reference text of the judgement on the urban quality of the built environment, in the connections caused by the movements and memories of each. On the contrary, every intervention is evaluated as if it were private, closed in its edge, confined, even when it concerns public buildings or, at the limit, transformations of street areas (for example in many urban design interventions). This attitude, implicit in the analytical and objectivist root of Enlightenment regulation, is reinforced and made binding in practice by the rigidity of the mode of production of projects and interventions. Everything contributes to confining the project: the ownership of the client, the incommunicability of public offices (e.g. ‘private building’ and ‘public works’, or ‘public building-public works’ and ‘public works-infrastructures’), the rigidity of programming policies and public financing, so that only with the recent Recovery and Redevelopment Programmes are the first, timid, procedures identified to connect interventions in the public space. Hence the risk of not having the right reference to the bases of investigation, which have the characteristics of a network and not of a single episode, of not recognising the continuity of the text that one would like to enhance, of breaking the sense of the city (and all its qualities in terms of identity, representativeness, serendipity, psychophysical well-being) into individual frameworks, considering each one oleographically resolvable according to internal rules, as if the quality of the individual phrases of a discourse accounted for the overall sense.

* finally, a determinant consolidated methodological guideline, the obligatory recognition of homogeneity as a value in itself, which supports as positive the practices of imitation, modularity, but also of model and typology and all the rules that induce them. The aim here is not so much to develop a general critique of these methodological approaches, but to denounce their implicit but very powerful role of antagonism to the valorisation of differential factors, of all those components of the city that constitute the signs recognised by few or all, in the complex of which, however, the demon of serendipity stirs, in whose singularities the genius loci stirs. With a normative tradition and a tendentially homogenising culture of intervention, one not only defends oneself from arbitrary baroque, from the mania for protagonism, from the devastating power of eclecticism in the hands of great transformers, but one also loses the difficult values of the ad hoc project, of the need for identity even in the consolidated city but expropriated by new uses: in short, one also throws out the baby for fear of dirt. Who can try today to give rules to enhance the singularity of sites, to increase the recognisability of consolidated situations, to organise the signs of identity of new parts of the city, when every expressive mode of the norm, every attitude of the institution, from zoning for building density to the via brevis so as not to upset the Superintendence of Cultural Heritage, is that of homogenisation, of adaptation, of design understanding with respect to the model, to pre-existence?

The picture, which I have tried to paint in dark colours, concerns the cultural environment in which we move, in which on the one hand widespread demand is formed, and on the other hand constraints of method and technique are tightened, rendering us powerless in the face of an obvious need, such as that of enhancing the city’s representative aspect, its aesthetic and architectural quality.

There is another framework to be specified, that of the physical context in which these rules (if we can enunciate them) will operate.

For the physical context, as for the cultural context, we are also faced with processes of different inertia and contingency:

* on the one hand, the factor of the durability of what is produced cannot be overlooked: buildings are placed in the city as a permanence, they are not correctable, they are at once text and context, shortly after their construction they are incorporated into uses as if they had always existed and endured forever.

This extraordinary disparity between the cultural temperament of the moment of production and the product’s permanence over time (through indeterminate other cultural situations) casts doubt on the possibility of conditioning with norms outcomes of representativeness, of sign, of effective message in any case, for the city of the coming centuries. Hence also the absence of a particular public interest in communicating uncertain values through architecture, certainly entrusted to a language resulting from the contingent situation. Conversely, hence the technical-idealistic stimulus to seek lasting signs, always representative of positive values, even in different cultural contexts and today unpredictable.

The physical permanence of buildings leads us to fall into the illusion of ‘permanent values’ communicated through their form, as if Architecture (the real one, of course) were a kind of Esperanto that allows us to send messages to unknown posterity.

* on the other hand, there is a specific stage in the process of producing the European city: the city is already there; in the coming years, barring catastrophic events, it will be adjusted and remade, but only to a lesser extent will it be enlarged. This has an important effect on our problem: the standards for urban quality are to be dedicated to completion interventions, to insertion in contexts (or rather in texts) that have already been transformed. Even the urban planning of future regulatory plans will in any case be an urban planning of completion, developing at an urban level the type of interventions that in building dominated the production of the 70s and 80s, filling in the B zones.

The trend is significant: in Italy in twenty years (1985 to 2005) building interventions on existing buildings rose from 20% to 80% of total interventions (in volume).

So rules must be rules to improve the quality of the existing city, and if they must resist the temptation to seek permanent values of architecture, they must still take into account the durability of the products they affect.

In order to be able to make a proposal, one must also hypothesise an outline of the socio-economic context in which these rules will fit, given the imminence of a second generation of urban plans, aimed more at urban qualification than expansion.

It takes little courage to envisage a future for urban transformative interventions caught between a few pincers, in which co-polarising and antithetical tensions polarise, hardly governable towards a single type of objective, but rather such that the range of reference values is opened up, so that the complexity of forces and desires can be harnessed to produce different and substitutable proposals depending on opportunities and resources:

-for economic pressures: on the one hand, widespread stagnation with inconspicuous re-use and reduced ‘extraordinary maintenance’ of the city’s public space, on the other hand, powerful operations of radical urban restructuring, linked to the transformation of production facilities or fringe areas, facilitated by complex public-private consultations that adjust plans on a case-by-case basis (in this direction, the procedure for PRUs and PRIUs is probably the first example not contaminated a priori by tangentopoli );

-for social desires: on the one hand, a residual, still unfulfilled demand for the ‘particular’, from the home-sweet-home with garden to the residential-tertiary-productive micro-mix of the ‘urban countryside’, on the other hand, the nostalgia for the City with strong signs, symbols, monuments, the desire to be a tourist at home, to applaud the Mayor and the Banner;

-for the demands of technical and procedural instrumentation: on the one hand, a reactionary deregulation to excessive bureaucracy, requiring a few very simple reference standards in the modalities of intervention, on the other hand, a practice of project-planning with different tendencies, from urban planning designed with architectural details to ‘virtual’ design resulting from new demanding regulations.

Effective rules in this multiform framework appear difficult to produce in an abstract way, without reference, even very diversified, to the real specific situations that city by city, neighbourhood by neighbourhood are taking shape in the range of social needs and economic feasibility, imposing a flexibility of consultation that the new rules will have to take into account.

In short, rules for urban quality appear difficult to produce, not only because we are incapable of doing so, but also because the situation appears, even for the good, to be very varied and protean. In this framework, our habit of making every status correspond to a rule prevents us from thinking up a simple regulation system that can be proposed to a user base enraged by the overabundance of useless rules.

Designers

Projects end up being in search of the umbilical identity of the object we make, and we no longer know to which system of signs, of senses, we belong. We know that public space is important, we just don’t know how to make it more pleasant given the great complexity of its perception. We know that we cannot make it pleasant with order and rules alone, but too often we orient our projects towards a narcissistic identity, without considering the participation of that building in the urban landscape as a strong element.

There is thus a lack of a strong characterisation to refer to for the innovative project: and this disorientation involves everyone, not only the designers, but also the users, inhabitants and tourists. Let us try and see where young people coagulate, where they identify the places that make cities such as Barcelona, Bologna, Lyon (just to cite well-known cases here) attractive to all Europeans: we will almost never find places designed to be representative, but more often we will find them mixed with different places, elected to the new role by chance, by contrast, for reasons that often escape us, or have in any case escaped the designers.

This is why it seems important to us to take note of the lack of a strong subject, to which we can refer and, far from being nostalgic about it, to investigate the reasons why we increasingly like consolidated urban landscapes, those in which identities that we no longer recognise have settled, those that are deformed (as in Zen culture) by unforeseeable events, those in which unforeseen actions can occur (think of the fortune of the square in front of the Beaubourg, or the infinite number of Italian meeting places).

So let us start from scratch, investigating the reasons that make us appreciate more the established landscapes, those in which identities have already settled. Why do we like not ordered places but those that have been completely deformed, in physical space or in the behaviour of users, places where unexpected situations can occur? In this perspective, of investigation in search of the engines of identity, the urban landscape interests us because there is an archaeological taste in the recognition of traces of orientation, which become, for everyone, stimuli for understanding the past.

To sum up, public space is appropriately the urban landscape

– to recover transversal, unforeseen personal identities,

– to offer the city to the curious gaze of the tourist,

– by archaeological taste of the recognition of mutually interfering sedimented orders,

– to satisfy the sense of serendipity in spaces and not just events.

All this has to do with the project, but it is very difficult to adopt a method and even more difficult to teach it: we should go to school in the East.

In any case, the galaxy of thoughts that I have mentioned here leads to some practical considerations that have an effect on the way we design: I set them out in summary points.

Firstly, a certainly fruitful change in design logic comes from placing ourselves in the right position with respect to the landscape we are helping to modify. It is not so much the attitude of designing a text within a context as designing a place in its complexity: the object we design is and will in any case be perceived as part of a system of places and is therefore, by definition, a contribution to the sense of the urban landscape that that place already generates before our intervention.

Instead of a “project-centric” vision, in which we imagine a user who always puts our project at the centre of attention (and perspective or photomontage), we need to be aware of the dynamics of the behaviour we plan to modify: what is in that place the model of fruition we are going to transform. From this it follows that our physical transformations are part of a flow of modes of cultural behaviour that are very slow to change and that, if they are to contribute to enhancing the sense of landscape, they must operate by small, coherent and non-traumatic shifts.

Following this cardinal principle, we can propose three tracks that are being worked on today:

– Enhancing the recognisability of places that are important for their role, but today lack appeal for meaning and memory. We are full of places mainly linked to a strong infrastructural system or to a consolidated and sedimented functional situation, but unstructured in terms of the urban landscape they generate. We transit a lot in these places: they are hinges of our way of experiencing the city, but they are hinges poor in recognisability. Many studies on American cities strive to redevelop these places-non-places, where the theme of identity has been at the centre of attention for thirty years; but often every hypothesis of qualification sinks into a poverty of cultural resources of the places that are completely artificial and ahistorically born from nothing, it is as if one had to oppose a process of desertification already in an advanced stage. Hence the importance of far-sighted actions, in order to avoid the formation of too strong gaps in the culture of places, of taking care as of now of the growth of representative places, even if minimal, in the urban landscapes in the process of consolidation, the need to enhance some places of the English diffuse suburbs, of the urban sprawl of north-eastern Italy, of the French habitat pavillonaire;

– Preserve, in the sense of bringing out the traces, support and spread the taste for an archaeological perception of the landscape. Being able to find traces of transformations and previous projects in every place and highlight them in their sedimentation and overlapping. To give them strength in as much as they can participate in the current urban landscape, even if they no longer have the power to bear significant witness to a previous order. Even the traces of old strong projects are often now rendered labile by sedimentation, but it is precisely the complex sedimentation that allows local identities to be interpreted and reinforced, much more than the original pre-established orders. In this sense, any prospect of restoring a pre-established order is often violence, while, on the contrary, enhancing the traces in their potential as suggestions and proposals is often a contribution to understanding, and to qualifying local identity in an allusive and seductive manner;

– innovate, a fundamental action where trivialisation reigns, where the sense of place has not been taken into account by those who have built, where there is actually a demand for identity. In our suburbs, made up of ancient gutted centres, starting with a few traces of reference, it is necessary for a new construction of systems of public spaces to take place alongside projects to recover the system of ancient signs. It is a matter of constituting a continuity of the newly formed urban landscape, which gives in a positive and appropriative key the sense of the greatest transformative event of the century, which is the widespread urbanisation. Probably in the suburbs the new sense of public space is not based on a perceptive continuity but on a reticularity, discontinuous over the territory. This continuity, to be interpreted not on a physical level but on a cultural and behavioural one, represents a challenge for our ‘historical’ sense of landscape, but herein lies the challenge of innovation to which the project is called, and it is opportune to accept the terms of the problem without pretending solutions that are no longer reflected in people’s behaviour (and therefore in their capacity to make sense).

Features of the urban landscape

Landscape is a factor of meaning

Landscape is the fruit of an interaction: that between the user and the outdoors

Natural landscape

Cultural Landscape

Urban landscape

Two actors

Identity of the insider

Curiosity of the outsider

Two methods

Analysis of space and urban signs

Holistic synthesis of landscape and place

Landscape and local identity

Networks and urban identity

fruition and serendipity

Modern public space is a network and cannot be relegated to individual places

Modern public space is not aesthetically producible or manageable without the contribution of private actions

Urban problems of our time

Crisis of local identity

Aporia of the relationship between builders and inhabitants

Prevailing dialectics between interests and equity over quality

How to distinguish in a continuum without denying it

How to consider the continuity of public space

Not recognising homogeneity as a value in itself

Rules and projects

The problem of management by rules

The problem of transformations through projects

No landscape design

Planned and unplanned public space

Contributing to the shaping of public space so that the urban landscape enables

– recover transversal, unforeseen personal identities,

– offer the city to the curious gaze of the tourist,

– enhancing the taste for recognition of settled and interfering orders,

– satisfy the sense of serendipity in spaces and not only in events.

– enhancing the recognisability of places that are important for their role

but lacking in appeal for meaning and memory

– conserve, in the sense of bringing out traces,

support and spread the taste for an archaeological perception of the landscape

– innovate, where trivialisation reigns,

where the sense of place has not been taken into account by those who have built,

where there is a demand for identity