Place, landscape and territory are united by being both subject and object of the action that is produced in the interaction with local communities. Individuals interpret the characteristics of a physical context, the same ones that participate in the definition of traits of their identity, and produce transformation actions. The outcome of the transformation will then become the new scenario that will host subsequent transformations. However, the three terms have slightly different meanings, so much so that they are often used interchangeably.

Place as a figure of certainty

Place, landscape and territory are united by being both subject and object of the action that is produced in the interaction with local communities. Individuals interpret the characteristics of a physical context, the same ones that participate in the definition of traits of their identity, and produce transformation actions. The outcome of the transformation will then become the new scenario that will host subsequent transformations. However, the three terms have slightly different meanings, so much so that they are often used interchangeably. We can say that by territory we mean the set of dynamics that shape a space and the space itself: a sufficiently large area over which the possession and overall design of a society unfolds. The term is ancient, of Latin origin. The concept of landscape, on the other hand, was born recently, born with modernity, as an intentional construction of a portion of territory, and contains a marked symbolic value for the specific cultural elite that represents itself in it, and is primarily concerned with open territory, with the transformation of the land into an aesthetic representation. Locus, too, is a term of Latin origin, which remains on a less defined horizon, more archaic, more radical, more general, less even scalar connotations, more ambiguous and rich, intimately polysemic. The term locus was used in a geographical sense to define a place, a locality, a position; or a connotated space, a farm, a field, a city or a region; but also a room, a dwelling, a lodging, and even a sepulchre, a tomb. Still in concrete, but not geographical terms, locus was used to define the specific passage of a book or article: a passage, a chapter, a specific theme of an argument. While in social terms locus referred to rank, consideration, social status; or to a particular circumstance, situation, condition; and again to temporal order, position, turn.

Place is not disconnected from the activity that an individual and collective subject performs. In a current definition of the term we read under the heading place: in general, part of the space that is occupied or that can be occupied materially or ideally.[1]The term place arises from the certainty of the solidary and rooted connection between subjects and space: they are one and the same and represent an identity whole with certain boundaries. No separation, choice or possibility is given. Place is therefore specific, complete, concrete. Place refers in geographical terms, in sometimes difficult and conflicting forms, to the certainty of possession, to the unambiguous overlap between community and space. A space becomes a place only after it has become the object of an affective, economic and symbolic relationship that manifests itself in an intelligible manner.[2] The place, regardless of the scalar dimension, is the context in which belonging is experienced, where it gives rise to something definite, perceptible, identifiable: in the place, the identity/identification relationship condenses into a concrete event. The place is therefore a figure of certainty that refers to and represents an identity that is still strong, defined and confining. For the place to exist, specific conditions must exist. If belonging and identification exist and these are manifested intelligibly, then place exists. Place is territory and landscape. Territory and landscape subject to identity dynamics, in which the terms of stability and continuity are present, manifesting themselves according to the characters of unity and difference. Otherwise, place does not exist.

It can be said that place represents the figure of identity certainty consolidated up to early modernity. Recent studies have investigated the sense of place in the era of the crisis of modernity. Some have highlighted the figure of excess: the non-place, others that of opportunity: the milieu.[3]

[1] Voce luogo, Dizionario Garzanti della Lingua Italiana, 1969.

[2] John Friedmann, in his essay Human territoriality ad the struggle for the place, confronts the various types of territoriality that occur in widely diversified contexts, but which are united by the essence of affective relationships: from the aborigines of Australia to the Torinese house where Primo Levi has spent all his life. Friedmann J., Human territoriality ad the struggle for the place, ‘Giornale del Dottorato in pianificazione territoriale’, n.1, 1990, p. 27.

Talune condensazioni incarnano l’espressività del territorio e hanno la potenzialità di diventare l’immagine della società insediata: i luoghi magici, simbolici, les hautes lieux. E’ questa la tesi argomentata da Bernard Debarbieux in alcuni saggi: Debarbieux B., Le lieu, fragment et symbole du territoire, in “Espace et societés” n. 82-83, L’Harmattan, 1996 ’Les lieux du territoire relèvent donc simultanément de l’ordre des matérialités, des significations et de l’ordre des symboles. Materiality because they are part of the reality of geographic space; meaning because, once identified as places, they are associated with values and therefore with spatial roles that conform to the ideology of the group that is territorialising them. Symbol infinitely, by virtue of the process, evisaged for a long time by authors such as Georg Simmel and Henri Lefèbre, by which the elements of geographical space can serve to symbolise the social by objectifying it. Simultaneously, then, the leiu localises, signifies and designates realities of another orde, a social group for example, or another spatial scale, the territory. Posed in this way, the question of scale gains in richness and complexity. Places are no longer simply elements of the territory; the figure of the territory no longer emerges only when they are all aggregated. The territory is present through certain places, which are perceived as having the capacity to symbolise it; thanks to this process of symbolisation, the scales are telescoped (…). ) that the advent of the territory, conceived as a social construct, presupposes that we take into account this capacity of the place to be simultaneously an element and a figure of it, its capacity to refer simultaneously to two spatial scales at the same time, its own and that of the territory in which it is embedded’. pp. 14-15; Debarbieux B., Du Hautes lieu en général et du mont Blanc en particulier, ‘Espace Géografique’ n.1, 1993 in cui argomenta sulla scoperta del Monte Bianco; Debarbieux B., Imaginer et aménager la montagne, Institut de Gèographie Alpine, Université Joseph Fourier – Grenoble, dove analizza la relazione fra l’invenzione delle immagini che riguardano la montagna in generale e la loro localizzazione specifica in un area denominata Lozère; inoltre analizza come le immagini che si sono susseguite nel tempo hanno inciso sulla pianificazione.

[3] Dato il carattere introduttivo del tema trattato non ritengo utile procedere in maniera sistematica per confronti con posizioni diverse formulate da vari autori; tuttavia mi preme sottolineare come in area anglosassone il tema dell’identità del luogo appaia descritta nei termini di sense of the place e come questo tema fosse già stato affrontato alla fine degli anni settanta da Edward Relf nel suo Place and placeness, Pion Limited, Londra, 1976.

Place, non-place, milieu

The first figure, the non-place arises within a new cultural dimension that Marc Augé defines as surmodern. Suramodernity, marked by the myth of excess, produces non-places that, by contrast with places, are non-identitary, non-relational, non-historical: airways, railways, aerospace, motorways, mobile habitats (planes, trains, cars), airports, railway and aerospace stations, large hotel chains, leisure facilities, and large commercial spaces are the spaces in which the characters of identity, relationship and history are absent. If in places, therefore, an organic social acts (affects, actions, passions, recognitions), in non-places there is a cold, passive and solitary contractuality, mediated by inanimate objects (signs, recorded voices, images), which keep the individual in the most complete anomie and solitude: airport lounges, motorways, stations are populated by screens, by signs (do not smoke, queue here, etc.). Where the anthropological place narrated its own identity and that of its inhabitants through handed-down traditions (rules of behaviour, common knowledge, landscape landmarks), the non-place tells of the common sharing of passivity, of delegation to others, of finding oneself in the condition of passenger, of client, of tourist led from one part to another without being able to decide.[1]

The second figure that of opportunity brings into play the concept of milieu, an ambiguous concept, even in its common meaning it means both centre and around. [2] In spite of or perhaps thanks to this ambiguity, which is closely affected by the contemporary identity crisis, the term has become in current use to define a physical context: no longer simply lieu, but mi-lieu.

The contemporary inhabitable space that the milieu interprets is no longer ascribable to the domain of certainty, it is no longer taken for granted that the physical context in which subjects conduct their existence produces meaning for those who inhabit it and for those who observe it. The milieu interprets the late modern condition of the end of the natural community and the advent of a new form of elective community that is structured around the terms of potentiality, interpretation, intentionality, and projection towards the future. In the milieu, that is, the relationship of possession (affective, symbolic, historical, economic) between the natural environment and the social environment is not inherent as in the place: the relationship is now only potential. If in the place the relationship with the physical context is implied, in the milieu it is made explicit: the geographical milieu arises from the encounter between society, space and nature.[3] The milieu is composed of an objective part, given by the inherited historical-environmental heritage, and a subjective part, given by the local society. The encounter between the two terms, however, is not deterministic. A two-way relationship is established between them, in which heritage offers potentialities that local society may or may not interpret according to a trajectory that, if aimed at valorisation, brings together the symbolic and the objective as in the transformation of matter into a resource.[4]

In order to make this passage explicit, Augustin Berque introduces the concept of prise, which he translates from the English affordance.[5] The grasp is simultaneously objective and subjective, its definition distances itself both from a merely phenomenological approach, according to which the existence of an object is given solely by the subjective perception of the object itself, and from the physical approach according to which a thing exists beyond interpretation. The term grasp brings interpretation and the risk of failure into play. The term resource still stems from an approach born of scientist optimism that envisages the generalised possibility of a universal gaze that rests on a matter and transforms it into a resource. Contemporary life, on the other hand, is open to risk: the territory offers potential that can perhaps be seen and well utilised. Indeed, holds, even if they are real, are never evident to everyone in the same way, they do not possess the universality of the physical thing.

Socket is invariant, but of variable consistency in its relation to the subject; it is substantial, but relative. Sockets become evident only when the specific characteristics of a context are recognised; they become evident when the relationship with the context is complex, when it brings into play affective and symbolic values, that is, when the subject is part of the context in such a way as to be able to grasp its intelligibility[6]. When the capacity to afford is lacking, the milieu does not exist. The milieu is not given, it does not exist at all. What is given are the characterising elements, the invariant potentialities constituted by the territorial, historical and environmental heritage, which may or may not be recognised and enhanced. The milieu only exists if the interaction with the observer is able to grasp the potential. In short, when the milieu becomes place again, that is, when in particular situations and for even minimal stability there is an identification between context and local society.

In late modernity, identification is not given, but chosen, desired, desired. In the milieu, potentialities are interpreted in the light of future desire, according to a forward-looking intentionality. The milieu also contains what it potentially has to offer and what it could potentially become.[7] The evolution of the concept of subjective identity and place therefore walk in parallel: the crisis of identity, as we have known it, corresponds to the crisis of place. In early modernity, place represented the coherent, time-stable and structured whole of local society and physical context. This certainty is now gone, physical contexts and local societies are generally no longer a coherent whole: everything is more fluid, nuanced, changing. Places are constructed in the negative: the non-places; or they become an opportunity for contemporary society to learn about, to grasp the potential that the context offers and make the best use of it: the milieu.

[1] ‘Alone, but similar to others, the user of the non-place finds himself with it (or with the powers that govern it) in a contractual relationship. He is reminded of the existence of the contract at the appropriate time (the way he uses the non-place is an element of this): the ticket he has bought, the coupon he has to present at the toll booth, or even the trolley he pushes through the supermarket are a more or less strong sign of this. The contract always relates to the individual identity of the one who signs it (…) The space of the non-place creates neither single identity nor relationship, but solitude and similarity. It does not even leave room for history, if anything it transforms it at times into an element of spectacle, most often into allusive texts’ Ibid. pp. 93-95.

[2]On the concept of milieu, see Francesca Governa’s book, Il milieu urbano. L’identità teritoriale nei processi di sviluppo, FrancoAngeli, Milan, 1997. The etymological ambiguity of the term milieu is rendered by the definition that can be found in any French dictionary. In the entry milieu of the French/Italian, Italian/French Dictionary Zanichelli (1993) we find: 1) centre; 2) around, natural and social environment; 3) middle in the sense of mezzo: to be in the middle; 4) mezzo in the instrumental sense of the term: by means of. Pierre George defines, while maintaining the ambiguity of the term, in the Dictionary of Geography the geographical milieu as: espace natural ou aménagé qui entoure un groupe humaine, sur lequel il agit, et dont les contraintes climatiques, biologiques, politiques, etc. retentissent sur le comportement et l’état de ce group highlighting the relationship between natural and social context in possibilistic terms.

[3] Augustin Berque defines the milieu as the relation of a society to space and ‘relation d’une société à l’espace et à la nature’ a relation that is at the same time ‘sensible et factuel, subjectif etobjectif, phénoménal et physique’ Berque A., Médiance de milieux en paysages, Géografiques Reclus, Montpellier, 1990, p. 9.

[4] Berque uses the example of oil to define the concept of a resource. I would like to quote Claude Raffestin who explains well the relationship between matter (nature) resource (culture) in his work, Per una geografia del potere, Unicopli, Milan, 1981 (orig. ed. 1981). According to Raffestin, ‘A resource is a product of a relationship. That being the case, there are no natural resources, only natural materials. (…) Without external intervention a matter remains what it is. A resource, on the other hand, as a ‘product’ can constantly evolve, since the number of properties correlated with utility classes can grow’ (p. 227). Raffestin cites the case of coal. ‘For a long time coal for human societies was but a material like any other, which could perhaps marvel at its appearance, but without any particular value before being integrated into a practice. Then, progressively more by chance than by science, it was discovered ‘what could be done with it’. That is, certain properties of it were invented’ (p. 226).

[5] To afford in inglese significa al tempo stesso: 1) permettersi, 2) offrire, 3) fornire. ‘It is what a specific environment provides (affords) to an observer who can (affords) perceive it because he himself is specifically adapted to this environment. ‘Affordances are properties (of the object) taken in reference to the observer. They are neither physical nor phenomenal’. Berque A., Médiance de milieux en paysages op. cit, p. 102.

[6] Berque defines prese as ‘invariant properties of the object (…) although they only exist as prese in and through a certain relation. (…) In short, they are mesological realities: neither the in-itself of phisics, nor the for-itself of psychology, but the with-itself of a potential that is realised in the relation of a society to space and nature’. Ivi, p. 103 (sottolineato mio).

[7] Sia chi lo osserva sia chi lo costruisce ‘cannot totally abstract what is from what ought to be: one cannot absolutely distinguish the is from the ought (as Hume would have said), the descriptive from the prescriptive’. Berque A., Médiance de milieux en paysages, op. cit. p. 33.

The late modern sense of place

If in the past identity was there, it was a certainty that had to be discovered, now it is something different, now it has to be consciously constructed. If in the past place was identity and represented a community, in the present place represents an opportunity, a challenge; place is imagination, it is project. The place, in its late-modern declination of milieu, represents a ‘stake’ made up of the new potentially universal values of memory and the environment, of the inherited territorial heritage, which offers the opportunity to experiment with the conscious, partial and incoherent construction of identity places.

Place today is an image to strive for, but it is also a risk exposed to failure. The inhabited space has taken on an entirely new value in late modernity. The late-modern place is not a certain and natural datum, inherent in the experience of the perception and collective action of local society; it exists where it is seen, perceived, recognised, it exists when a form, even a partial one, of civil coexistence linked to processes of common use of the territory is reconstructed.[1]The presence of place is therefore fragmented, but necessary. The territorial heritage inherited from history plays an important role in defining the identity of places, but its effectiveness is increasingly linked to the continuous interpretation of meanings by the agents: the place does not exist in itself, but only if it is recognised by the community that populates it. The consequence is that the place takes on a new and unprecedented value in late modernity: where in the time of slow rhythms it was established as a mediator of knowledge operated unconsciously, the place asserts itself in the framework of the contemporary condition as a consciously sought mediator of knowledge: thus as the outcome of the project. If in the past, therefore, the place could be considered a ‘given’, a condition of origin, a certainty, in contemporary times, the place is an arrival, it is a condition to strive for, it is a project, it is a collective invention. The late-modern identity place is the outcome of a project. Place today is a challenge.

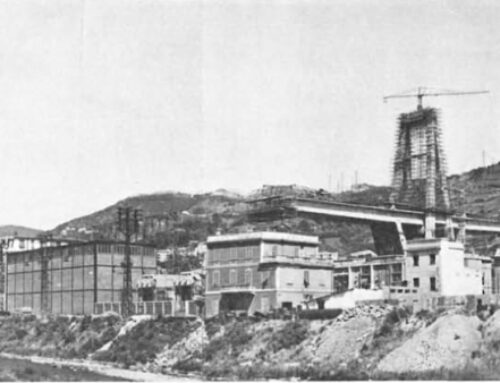

As shown in Diagram I in the past, the place consolidated its existence in a slow process of cyclical learning, of direct observation and continuous verification of the appropriateness of territorial actions, which sedimented customs, wise rules for the use of the environmental resource, that is, it created a local heritage of widespread knowledge, a local genetic code, an active memory that was handed down through the practices of social life. In the past, care was inherent to the possession of the place in both its declinations (availability and ownership of a good). Every innovation that came from outside was filtered by the genetic code that produced a localised interpretation and experimented in context. The innovation, after being experimented and having had time to evaluate its effectiveness, became a stable innovation, a territorialising act, which fitted coherently into the original context, guaranteeing a dynamic stability of the environmental resources and an evolutionary coherence to the landscape text.

Scheme II shows how the actions of de-territorialised social actors – considered all, external or internal, as outsiders insofar as they do not activate any practice of care towards the place, but only of use, coming from a general, a-contextual custom – generate social labilisation, and therefore discontinuity in passing on information and use resources ignoring the limits imposed by the environmental system, sedimenting inexperience. Innovations from the outside are not filtered by the local genetic code and produce deterritorialisation that manifests itself in the evolutionary inconsistency of the landscape text and the dynamic (and therefore ever-increasing) instability of the environmental system. The continuation of these relationships over time generates the destruction of the genetic code and constructs non-places.

In the contemporary world, place does not exist naturally, but only in fragments where a wise and conscious use of resources has been consolidated, where islands of active knowledge have occupied and produced territory. The practice of caring for and knowing place totally disrupts the alternation between insider and outsider. The categories of insider (the insiders of local society) or outsider (the outsiders of local society) are ineffective with respect to the identification of the late-modern category of possession not linked to ownership, but to the recognition and common and wise use of potential (milieu). The insiders (the insiders, those who have long resided in a place) may be de-localised, i.e. they may not enter into any cognitive and active relationships that bring into play the values of representativeness and symbolic value, while the outsiders (those who come from outside, from afar, recent residents, or simply entrepreneurs who do not live in the place) may advantageously interpret the local potential. The principals of a design aimed at reconstructing symbolic and representative value in the territory are therefore those who we might call care-takers, i.e. the subjects, resident or not, who act according to a localised logic. These are those who recognise the multiple values of a place, and for this reason love it (they are willing to create a relationship with the place itself that is dense with meaning), and consequently take care of it. The place today exists only where it is cared for, regardless of the type of ownership to which it is subjected: it is not the insiders or outsiders who own the place, but only those who care for it, those who know it, those who continually reproduce it, whether inside or outside the settled community.

Place therefore takes on an entirely new value in a society exposed to multiple possibilities, the progressive weakening of social ties, the sublimation of cognitive experiences, and the globalisation of personal geographies. The construction of a future society that is open but aware, that redefines its own identity also passes through knowing how to use the symbolic and material values of the place to rebuild social ties, to make the place once again a ‘womb that welcomes’. The place in this vision plays a central and marginal role at the same time: it is central as an opportunity because it becomes the substrate on which to build a social bond, but marginal because the bond is limited. The collective possession given by care practices creates social cohesion, but does not involve the existential definition of individuals. Place today does not define a solid community with a strong identity, in which the shared territory represents the symbolic object of identity, it represents that important but partial part of the shared social identity.

Planning today finds itself unprepared for this sudden change of scenery. The territorial project cannot in fact be hypothesised as the ‘bureaucratic machine’ of plans that still regulates sectorial flows (environmental, traffic, goods), but is instead a project, inevitably complex and complicated, that attempts to reconstruct relations between the settled society and the context of reference, aimed at increasing meaning in the material production of acts. The late-modern project abandons the perspective of certainty that wants to subject the territory to the control of a single gaze, but follows the fragmentation of the spontaneous reconstruction of places.

While it is necessary to place limits on the exploitation of environmental resources, the role of forms of social communication, which create a shared sense of place, becomes central, starting however with the introduction of the active and visible presence of space in common into the social dynamic. It is a matter of constructing the scenario where the play of the planning community is activated: a common scenario that tells what is around to those who are no longer able to see because the landscape is illegible, because speed prevents them from looking behind appearances, because everyone has forgotten.

[1]Paba G., Luoghi comuni, Franco Angeli, Milan 1998.

The tools of common space staging

Designing territory today and not standards means abandoning the habit of the self-referentiality of the plan, which identifies its legitimacy at one extreme in solipsistic poetic intuition and at the other in the scientific nature of data. To participate in the identity project of the place is to enter the midst of a game of mirrors, in which one looks at, interprets and transforms what has already been looked at, interpreted and transformed. It is the form of territoriality, the rules that each society decides to give itself with respect to the territory that hosts it, that can make us understand with which eyes the characteristics of the place are looked at and interpreted. It is necessary to follow two parallel paths: on the one hand, to resort to documents that preserve traces and, of the interaction between context and society, with stories, narratives and textual descriptions in which it is possible to glimpse the historical conformation of the place, but decisive for us are the images, the graphic representations, which contain the form and its representation, in the light of the values, culture and beliefs of the time. On the other hand, it is necessary to rediscover a direct contact with places and current owners of places. The territory project needs both a dense reading capable of restoring depth and depth, and a client, even a hypothetical and imaginary one, who allows the course to be estimated.

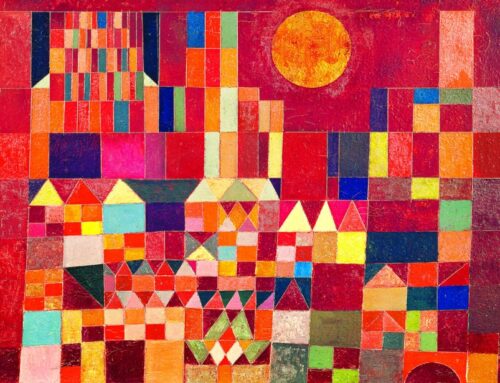

This is why the most convincing image of place today is one that abandons the rigidly functionalist approach of the systemic paradigm. Some, for example, consider systems theory ineffective for urban planning practice, favouring the concepts of background knowledge, concrete systems of interactions, rationality of games, descriptive and action planning.[1]Others, on the other hand, see in it certain flaws of origin, such as reductionism, mechanicism and generalised control that direct the perception and descriptive form of the problem itself. [2]Others still prefer to refer to softer metaphors such as theatre or play, which are useful for effectively defining the social relations involved in the designation, conception and representation of the landscape, which can be traced back to Geertzian interpretative anthropology.[3]The image of the theatre is particularly evocative and contains at the same time the idea of the scenario and the actors who stage and bring to life the space that contains their acts.

For urbanists, the construction of places with meaning means participating as actors in the more general process of identity reconstruction that the industrialised world is going through. Reconstructing places means abandoning the modern outlook that sought a universalist, univocal and certain project, but it also means abandoning the postmodern theory that unconditionally accepts and often exalts the emergence of a fragmented individual, without an identity, without a centre, without a principle of order, who disperses himself in the universality of the indistinct, and who ends up identifying himself in the scattered suburbs that resemble him.

Equipping oneself to design places means taking one’s toolbox and looking inside, seeing what is still needed, what is to be thrown away, but much more it means digging into the depths and rediscovering old tools, considered rusty and obsolete but which with the passage of time come back in handy, and are found to be still usable. Designing requires looking with a new optic, one that abandons grand interpretative models and more subtly turns to understanding the social practices that represent the shared space (current ones, past ones, innovative ones). The change of optics also uses tools of general interpretation, without falling into mere idiographism, but starting out again from the interpretation of uniqueness, specificity, the identification of local morphogenesis, from the many and contradictory micro-histories and not from grand narratives that superimpose certain, univocal and general rules on contexts. It is from the perspective of the local that the general acquires meaning, in the contemporary world ‘only by starting again from the leaf observed under the microscope is it possible to save the most abstract and regular principle of the network’.[4]

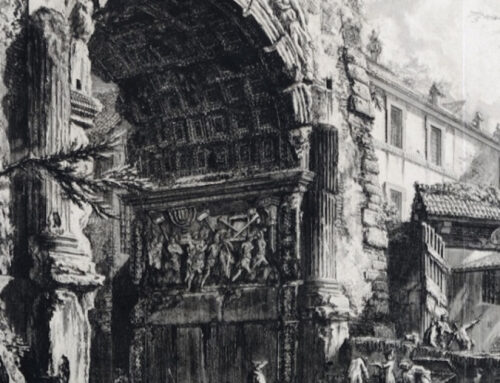

In the bottom of the box, one can perhaps find a tool that urban planners have long used in a simplified manner, and which may once again be extremely necessary today: representation. Iconographic representation is an ambiguous and rich tool, telling of many things, holding together places, images, actors and intentionality. It has been the principal way of representing the world and representing oneself in the way, through the interpretation of the powerful and the hands of artists. The maps of cartographers and the images of painters described the world, but at the same time, by interpreting it, they designed it. Representation is one of the useful tools for the actual construction of place, because it allows, in its conciseness and complexity together, to ‘see’ it, to imagine it and to put into practice actions to build it, but it is also a dense document, the careful study of which reveals the historical identity of places. To rethink the role of representation is to try to build a bridge between the world of geography, the ancient science of the courtly description of the territory, and town planning, heir to cartography, which today sees the territory only through the image of the norm.

[1] Palermo P., Interpretations of urban analysis, op. cit, p. 163.

[2] Wolfgang Sachs states in this regard: ‘Next to the concept of “integration”, the concept of “system” represents a key element for the representation of a global system of interconnections. But beware, systemic language is not without fault, as it directs perception in a technicist manner. To consider living communities as a ‘system’, be it the pond at the edge of the forest or the planet Earth, is to try to determine a minimum of basic components and to represent their mutual dependencies according to numerical ratios. In the case of the pond, the system could consist of a connection between energy, mass and temperature, while in the world system it could be population, environment and resources. It is not possible to explain or predict the behaviour of the system differently. This reductionism is unavoidable: the systemic language cannot give up grasping the totality of the point of view of their control, so much so that it has been the language of engineers and managers since its origins. The system concept was discovered in the 1930s to describe organisms with mechanistic objectivity. The ‘whole’ is interpreted as ‘balance’ and the relationships between the whole and its parts, in the manner of mechanical engineering, as self-regulating mechanisms that serve to maintain this balance. By knowing the feedback mechanisms, the behaviour of the system can be simulated. The discourse of ‘ecosystem’ or ‘global system’ cannot shake off the legacy of the engineering sciences, as it too is dedicated to management interests’ Sachs W., Archeologia dello sviluppo, Macro Edizioni, San Martino di Sarsina (FO), pp. 36-37.

[3] Quaini M., Rappresentazioni e pratiche delo spazio: due concetti molto discussi fra storici e geographi, in Galliano G. (a cura di) Rappresentazioni e pratiche dello spazio in una prospettiva storico-geografica, Brigati, Genova 1997, p. 8. The text by Geertz to which Quaini refers is Geertz C., Anthropologia interpretativa, il Mulino, Bologna 1988.

[4] Quaini M., Representations and Practices of Space: Two Much Discussed Concepts between Historians and Geographers, op. cit.

Territorial biography as collective representation

Those who practise the interpretative dimension of the project are often far removed from the world of experience and the common life of the inhabitants, which it is not enough to ‘listen’ to know, but which requires a shared path in which a new common sense is reconstructed. Experts give back their personal interpretation, exalting the architect’s ‘poetic doing’ and aestheticising, vice versa the experiences of participatory planning – interested in giving voice to all the inhabitants, even the weakest and least recognised – are crushed by the difficulty of making the different interpretations of the territory dialogue in a public dimension, in the absence of an interpretative image of the place. In those meetings, there is no one to reconstruct and give voice to the place, no one to tell its story, no one to show its propensities for transformation, its resistances.

There is a lack of a link between these two worlds – that of poetic interpretation and that of participation. Even in the most careful experiences, the relationship between the world and the ‘image of the world’ that the community constructs or is willing to construct for itself is missing. The ‘world’ is more often than not designed from the outside: the observer is not part of the group, even if he or she produces interpretation from societal behaviour, and those who are part of the group do not express the sense of place through image. What is missing today is the visualisation of the shared space where the shared sense of existence is constructed. To put the place – in its deep dimension of time, sense and space – in the middle of the planning community is to forcefully introduce into the discussion what is normally ignored.

Spatial biography reconstructs the identity of a place, reconstructs it in the present, looking for limits to its transformation, looking for new identity boundaries, not abstract constraints, but limits of meaning that arise from the knowledge and actions of representation. Biography ‘represents’ space in common, reconstructs facts and events, gives more weight to some moments in history, ignores others.

Biography is both local and global, but it is both local and global from the local. Biography is a perspective of meaning and verticality that narrates the structuring over time of a place, of its personality as it has been built up over time on the basis of relationships and experiences far and near. It is necessary today more than ever to start again from the leaf, from the local, in order to understand the tree, to avoid the abstract and all-embracing grid of the macro being projected onto the place. Biography is therefore not a micro-historical-geographical reconstruction, naively descriptive and empirical, of perceptive derivation that skips the reconstruction of the relational context (social, economic, environmental, cultural). The biography wants to be part of the general relational process of identity reconstruction starting from the interpretation of the network that has produced the personality of the place. ‘Only after looking at the leaf under the microscope is it possible to save the most abstract principle of the network’.

The narration of events and the life of places is a necessary tool to restore depth and meaning to space that has lost its memory. Storytelling is an interactive tool: you talk, listen and continue the tale, creating new stories and images that follow a common thread. The intentional planners of the place will look in the ‘scattered nuclei’ of identity reconstruction for the wise men of the late modern tribes who have already staged acts of biography.

The representation of past forms of territoriality does not simply transcribe in graphic form the descriptions of historical geographers, or landscape archaeologists, but is a tool that reactivates the function of memory, selecting and choosing what to remember and what to forget: it is a path of rediscovery in the past, oriented towards future reconstruction. A non-documentary tale, but a tale constructed in the present, a tale born of interpretation that re-reads history and re-actualises it, uses it for what is needed today, emphasises and consciously chooses. A tale whose purpose is to be continued in the present, like fairy tales that are passed down orally and manage to fit into the contemporary. And like fairy tales, which are written in a way that is persuasive and comprehensible to the listener, the drawings narrate places in a way that fascinates the beholder, with a technique that is comprehensible to the eye and the mind, so that topography and chorography, separated by Ptolemaic geography, walk together.

The central elements of the biography are given by time, hence by tracing the transformations, changes, and resistances in significant historical phases that are not evenemmental, but marked by changes in mentality; by meaning, by the understanding of the meaning and role attributed to the objects deposited in the territory; from the continuity and thus the morphogenesis of forms, from the resistance and continuous reproduction of forms through the filter of the local genetic code; and from an ambiguous local/global pictographic language that uses the geometric information from centralised geographical institutes, but submits it to local calligraphies, in order to relate to the common sense of places.