Contemporary inhabitants are not fully aware of the historical depth they tread upon and find shelter in every day: the archetypal figure of the ruin dweller is largely unconscious, the tragic aspect lies precisely in the coincidence of cultural distance and physical proximity of the inhabitant with the signs of ‘his’ unknown history.

Most Europeans and many others in the rest of the world today inhabit ruins, i.e. they move daily in contexts marked by traces of historically sedimented artefacts, most of which have lost their relationship with their original uses and behaviours. This is true for those who inhabit urban centres or much of the ‘urbanised countryside’ and in general for those who move along major traffic routes. Contemporary inhabitants are not fully aware of the historical depth they tread upon and in which they find shelter every day: the archetypal figure of the inhabitant of ruins is largely unconscious, the tragic aspect lies precisely in the coincidence of cultural distance and physical proximity of the inhabitant with the signs of ‘his’ unknown history.

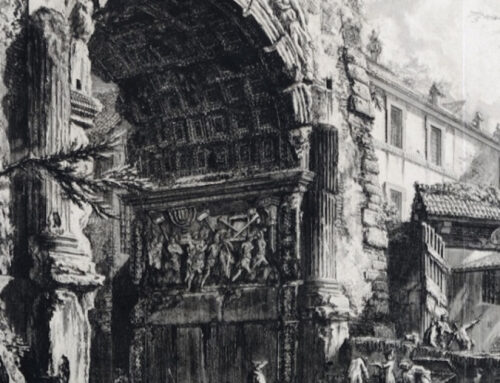

In the middle of the desert, in the Atlas Mountains, there is an ancient Roman city that history does not remember. Little by little it has fallen into ruin, for centuries it has had no name: it has had no inhabitants since no one knows when, the European has so far not marked it on his maps, because he did not suspect its existence…. Through a Roman triumphal arch, past two dry palm trunks, one reached the ruins of a wall whose ancient destination could no longer be recognised: they were now the home of Aaron, the father of Obadiah [1].

In just a few lines, at the incipit of a perfect tale, Stifner’s romanticism outlines an archetype: inhabiting ruins, that is, producing, through direct contact, a palingenesis of meaning in things that endure but that ‘history does not remember’.

Like Obadiah’s father, most Europeans and many others in the rest of the world today inhabit ruins, i.e. they move daily in contexts marked by traces of historically sedimented artefacts, most of which have lost their relationship with their original uses and behaviours. This is true for those who inhabit urban centres or much of the ‘urbanised countryside’, and in general for those who move along the main traffic routes. As in the nineteenth-century tale, contemporary inhabitants are not fully aware of the historical depth they tread upon and in which they find shelter every day. On the other hand, the archetypal figure of the inhabitant of the ruins is largely unconscious: indeed, the tragic aspect lies precisely in the coincidence of cultural distance and physical proximity of the inhabitant with the signs of ‘his’ unknown history.

Augè points out that ‘in the countries in which the ethnologist traditionally works, ruins have neither a name nor a status. They always have to do with Europe, which is sometimes the author, often the restorer, always the visitor.”[2]

Thus, ruins become heritage only through a re-awareness, a new appreciation: without a gaze that enhances them, they are inert matter, rubble. The ruins therefore play a cultural role for the user: to understand their significance before the stones, we must investigate the mind and the eye that looks at them.

On the other hand, it is in the subjectivity of the gaze, as we know, that landscapes also take shape, the relationships between the things that surround us acquire meaning. Landscapes too are the result of interpretation and qualification of places, they are pieces of territorial matter, subjectively perceived as meaningful.

Beyond the personal, biographical sense that places and things can arouse in each of us, what interests many psychologists, philosophers and anthropologists is the ‘common sense’ that is generated for ruins or, by similar processes, for landscapes. It is a common sense that is not entirely dependent on literate culture, learned at school or on TV: it is a way of knowing that seems to be rooted in deep and structural relationships, emanating senses that are not encoded in an organised way but are deeply engrained in our cortex as Europeans. In fact, in general terms, the common sense of both landscape and ruins involve relationships

a, between man (or his artefact) and nature, highlighted by Simmel in the early 1900s [3] but already intriguing throughout Romanticism,

b, between affections for things and time, the unequal perception of which (by each of us or each of our cultures) is one of the great removed problems of the 20th century,

c, between things (or landscape) and transformative action, with or without a project: another of the themes that are well present in reality but difficult to discuss in their roots.

It is precisely on these relations, perhaps ‘symmetrical’, that a profound reflection can be developed, involving both the sense of ruins and that of landscape.

a. Man and his artefacts vs. nature

Simmel places ruins at the centre of the relationship between nature and the work of man, outlining the subtle fascination of ruins as the basic seduction of vitality that overcomes the petrified block in the artefact: we are captivated by the image of ‘nature overcoming the spirit’: a sort of revenge of renewing natural energy, which finds different and antagonistic ways of manifesting itself to the closed form that civilisation imposes with its artefacts.

It is evident that this dialectical effect is produced by a pictorial gaze on the landscape: one is reminded of the countless canvases that, from Mannerism to the 19th century, first compose and then dramatise shots with a peaceful backdrop of trees and water around the legible but intact remains of buildings from another civilisation.

Formally, the effect is achieved by contrast, between nature that ‘detests the straight line’[4] and the pitiful fragments of ancient geometries, still strong in sign but incomprehensible because they are now reduced to syllables that are randomly removed from the planned discourse to which they belonged.

Simmel emphasises that the overall sense of the ruin is new, not the evolution of the initial sense of the building. This implicitly means that it is no longer a question of ‘ruin’ but of ‘landscape with ruins’: the formation of a new sense is assigned to a landscape ensemble (of invention), to the relationship between incongruous parts aroused by the gaze imposed by the picture.

One often notes the cunning of the painter of landscapes of invention, who ‘artfully’ inserts details and contrasts into the picture, mostly centred on the ruins: the shepherd encamped, the capital in the foreground, the sheep grazing among the fallen columns. But to modern eyes, such artifices appear cloying and end up distracting from the true centre of attention: the sense that the ruins only acquire in the landscape, no longer as protagonists but as comprimarios in a casual relationship with the uncultivated and overbearing vegetation, a new meaning emerging precisely because they have lost their original sense as things in themselves, they can no longer be read as buildings resulting from an organic project.

It is the revenge of the subjectivity of the gaze, which recomposes a posteriori a new meaning of the landscape as a whole, perceivable because it is revealed by the deconstruction of the parts that previously imposed a priori meanings, assigned by the holism of designed things. Finally, the ruin makes it possible to overcome the ‘blocked’ sense of the built, which when intact takes itself out of context: it denies its belonging to the general sense of the landscape. Only time, by ‘chewing’ the buildings, allows them to be metabolised in the landscape, which ‘in peace’ can ‘digest’ them.

In this potential for a posteriori recomposition lies the interest and emotion that Barthes assigns to the ‘punctum’ of photographs. For Barthes, it is ‘a detail (that) comes to disrupt my whole reading; it is a vivid change in my interest, a thunderbolt. Because of the imprint of something, the photo is no longer an ordinary photo. This something has tilted, it has transmitted a slight vibration to me, […] that pierces me beyond my superior consciousness. […] From my point of view as a Spectator, the detail is provided by chance and without purpose; the picture is not at all ‘composed’ according to a creative logic. […] If certain details do not sting me, it is undoubtedly because the photographer put them there intentionally. […] The detail that interests me is not, or at least is not strictly, intentional, and probably must not be; it is in the field of the thing photographed as a supplement that is at the same time unavoidable, unintended.”[5]

As we read, the excitement induced by the ‘punctum’ of the photograph (similarly to what happens in the real landscape) is produced by a seizure of the power of the viewing subject over meaning. The beholder disengages himself from what is proposed and finds his own emotional path to signification, exploiting, like a free-climber, handholds that are encountered by chance, in a way that is not preordained by anyone and unpredictable to rational investigation.

When visiting an archaeological site, in that uncultivation due to the unkemptness and poverty of resources to which we are accustomed in Italy, there are infinite opportunities to perceive the ruins that can constitute an exciting ‘punctum’, a clue that refers to an intriguing exploration: like tackling a rebus I construct a new meaning in things that apparently tell me something else. It is important to emphasise that the ‘punctum’ excites because it is not a matter of reconstructing rational messages (‘of the higher consciousness’ says Barthes) but of emotionally grasping new unexpected effects. We are at the heart of the pleasure of exploring: one of the prime movers of tourism, the impulse that (with identity and the sense of the sacred) drives one to landscape.[6]

In short, ruins fascinate because they are pieces of broken chocolate eggs in the landscape’s ragamuffin: they are precious material for new explorations of meaning, not banal nature, still endowed with an evocative form, but deprived of the peremptory aspect of the complete building, which would prevent a free interpretative interactivity of the beholder.

But the subject play can be extended to any place: the great photographers continually chase this kind of sunspots in the sense of the landscape, they catch the sign when they show the flaw in the designed communicative system, when the relations between things open up to new interpretations. Thus, in fact, Fontana or Jodice portray the territory as a repository of potential ruins, of apparently accomplished objects that reveal themselves shattered to the eye of the lens, ready to recompose themselves in forms given by new associations, thus suggesting hidden identities and unpredictable surprises.

b. Affection for things vs. time

If one of the conditions that liberate the gaze on things is their spatial shattering with respect to the strong design of the original project, certainly the same applies to the other vital axis: time.

The form of time, as we describe it in our historical phase, appears as a continuous flow and we have a sacred respect for its regular, undifferentiated scans. It is an Enlightenment remnant of the ‘metrisation du monde’, which has survived the advent of the plural and subjective society because of its unquestionable instrumental value: the homogeneity of the flow helps the machines of the world to function together. But in reality we perceive (both personally and socially) time, like space, with profound discontinuities: great stasis with regular cyclical sequences or sudden acceleration with traffic jams of events that alter our habitual rhythms. It becomes clear to any realistic investigation that our histories, personal and collective, are not stored in memory as the result of systematic sedimentation, but with denser cores of information or long meaningless intervals in memory.

On the other hand, memory and oblivion are considered complementary factors for personal and or social psychological equilibrium, as Ricoeur passionately recounts.[7] Especially in the face of painful wounds, the process of healing and forgiveness, often desired, passes through oblivion, risky but necessary. Ricoeur brings out the dilemma of our generation, which sees the last witnesses of the tragedies of the 20th century fade away, and is torn between the continuity of memory ‘so that they will not be repeated’ and the novelty of rebirth, which comes more easily if it reduces the weight of the oppressive burdens of the past.

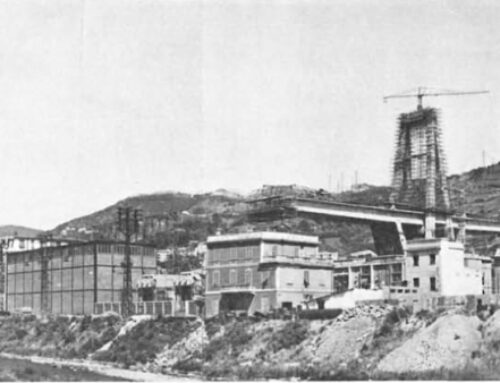

The landscape figures of time are condensed in the signs of discontinuities, of crises: the landscape does not signal the ordinary flow of time, but presents, with ruins and rubble, the material outcomes of traumatic events. And people behave differently in the face of rubble and ruins: sometimes making the remains sacred as a testimony in stone of blood, in other cases processing mourning into oblivion and erasing traces in cities as nature does in forests.

Belpoliti focuses his reflection on the collapses, on the years at the turn of the millennium, marked rather by rubble than ruins. For him, the collapse of the Berlin Wall marks an extraordinary opening in communication between two cultural universes, the collapse of the Twin Towers on the contrary marks the closure of a potential integration process [8].

But in the face of that rubble, Berlin and New York are reacting as a healthy body does in healing a wound: they reduce the mark, they prepare for metabolisation and thus oblivion: hardly a trace remains of the Wall, Ground Zero is preparing to be the foundation of a new skyscraper. Cities work to heal living traumas, and therefore reduce the time of the rubble as much as possible.

So rubble plays a different landscape role from ruins, it is the remnant of an action that wants to be concluded, while ruins are a point of arrival, an aftermath that has definitively lost contact with living history, and now stands in the landscape marking an unfathomable discontinuity in time. In front of the ruins I can do nothing about it, while in front of the ruins if nothing else I am indignant, I cry, I am still involved and turned to the past. Benjamin, shortly before committing suicide, draws a bitter reflection from this powerlessness in an age of rubble (which he calls ruins) and intuits an unbearable force that turns away from the past, from pietas, from remembrance: it is a force that comes from paradise that forces the angel who would like to dwell to turn away from the signs of catastrophe. [9]

If the contemplation of the rubble blocks and depresses, that of the ruins can be liberating because it bears witness to another time, which no longer has anything to do with my life except through my elaboration, my reinvention of places: it has become a resource for the future because it has detached itself from the involvement of the past and made itself available for my reflection.

The process that transforms rubble into ruins is linear and non-traumatic, and is linked to the passing of generations: the remains are the instrument of memory, as long as it is vital; they are the vehicle of emancipation from memory, when there are no longer any living people left to remember directly.

Things help to slow down time where memory is alive and every aspect linked to the past resurrects its context and landscape in the imagination of those who lived it. Conversely, things help to suspend time when the kaleidoscopic reflections of living memory end and objects, now opaque, are no longer a past that is still present but a symbol, a fragment of an unrepeatable world.

As with the project, the ruin detaches a piece of reality from its original condition and reintroduces it as a new and rich resource available to the beholder and his subjective culture, here and now. They come to us cleansed of blood and toil, like frozen meat, far from the trauma of butchery, perhaps for this reason more edible to our hypocritical tastes.

With this in mind, we could say that we see as ruins not only the stumpy and collapsed parts, but entire complexes that are intact but lacking in landscape and living memory that maintain the original relations of their use and their role in the territory. They are therefore for us ruins, resources for the future, not only the Colosseum but the Mezquita, industrial archaeology and terraced slopes for crops now abandoned.

This generalisation should not seem at odds with Woodward’s theses, which assign a main place in the bundle of ruins to their sense of unfinishedness. [10] In our view, creativity and imagination is not stimulated by the fragmentary appearance so much as by the formation of a new landscape between the object of the past and the new context (or the new gaze). The ruins generate another sense, different from the original one, supported both by the different context in which they are placed and by the renewed thought and culture of the beholder: in short, ruins are activated where new landscapes are formed.

c. New landscapes and ruins

For those working on landscape and territory, it is also intriguing to consider the complementary hypothesis: not only do ruins play an active role where ‘new’ landscapes are formed, but ‘new’ landscapes are founded on ruins.

With Guarrasi, we argue that the new focus on landscape is a cultural and ‘political’ issue, animated by a socially widespread demand for distinctive marks on the territory, both of novelty and identity. [11] In our time we are witnessing the reawakening of the landscape and the monumental sign (which of the landscape is the exclamation) after a long eclipse that brought other priorities (the city, roads and houses, one might say) to the forefront.

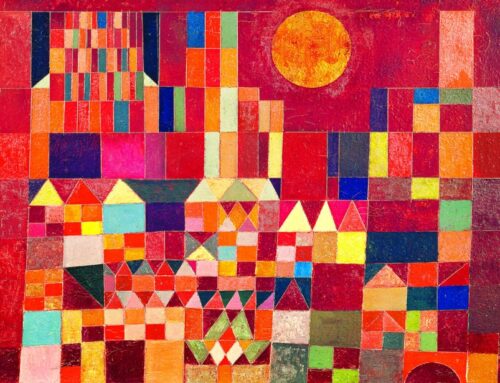

The reawakening of the role of the landscape, however, requires cultural resources, raw materials that are not shapeless but pieces to be recomposed, hence history as a smoothie, or rather as a minestrone in which to fish out the ‘old’ signs that make up our ‘new’ subjectivity: one would like to have the gaze that two hundred years ago only the King had, and that made his architect reconstruct landscapes with ruins.

At Virginia Water in Sussex, a tourist sign describes: ‘These ruins were erected on this site in 1827/ by King George IV/ having been imported in 1818/ from the Roman city of Leptis Magna/ near Tripoli in Libya/ Danger-Do not approach’. [12]

The diffusion of the ingredient ‘ruins’ from the places of eccentric aristocratic pleasure into the territories of our everyday landscape practices is one of the symptoms of the complexity of the system being formed in times of democratisation of cultural affects. Almost infinite possibilities of expansion of cultural references have opened up for all of us: we can make ourselves the landscapes we want, travelling (or surfing the Internet) and above all with the cultural references we choose, more or less at random.

In this sense, ruins are a highlight of the fruit salad of references we refer to when constructing our landscapes: they are a product of that rhizomatic and reticular postmodernism that has been spoken of with suspicion for 30 years. [13] The diffusion of the postmodern way of behaving towards culture and knowledge entails the eclipse of order and systematicity not so much as a structure of knowledge but for the orthodoxy of sources, the hierarchy of references, and the formation of value criteria assigned, in the landscape, much more to ‘syntactic’ and synchronic aspects than to the ‘paradigmatic’ ones of traditional cultural reference systems.

The gaze of one who is intrigued by the ‘new’ in the landscape looks for seeds to grow in HIS subjectivity. For that gaze, ruins are a sort of ‘stargate’ for an intuitive, ungrasped suggestion of the past: like a seed, it is considered a fragment of the lasting structure of the territory, to be placed in a new cultural and landscape context. In this way it develops, generating new effects in the landscape, still linked to the deep structure of the territory but evolved into new meanings, which today become a lever to remove the banality of a territory that appears without signs and without dreams.

The ruins of the past (as well as the ‘ethnic’, oriental or African reference) are therefore thought of as pioneers of a new colonisation, components that come from far enough away to help dismantle the hierarchy of recent but consolidated signs and metabolise new meanings of the landscape in new contexts.

The recourse to the references of signs distant in history has been repeated many times, always on the basis of the same operational sequence: the signs of declining civilisations are taken up and resuscitated in new contexts, forming the distinctive character of new landscapes. The pronaos of the ruined Greek acropolis are taken up again in imperial Rome, these demolished ones are discovered in the Renaissance and reinvented (not so much by Alberti, who reproduces them too structurally, as by Palladio, who reinserts their language in the Venetian countryside, of noble villagers); On their social weakness, neoclassical Enlightenment dreams are generated with new lifeblood; these, stripped of their ideal content, clothe 19th-century sacred and profane public works (or the distinctive features of the residences for the American rural aristocracy); again, their now tarnished splendours are multiplied in the infinite refractions of the postmodern.

In short, time and space help to weaken the too ‘hard’ and self-referential cores of designed complexes and make innovations possible only if the physically structured relationships alter and lose their vigour.

Each time, the model must be shattered, reduced to ruin in order for the evolutionary structural factors (long-lasting because adaptable) it contains to come to light and be of interest to new interpreters.

This only happens if the new interpreters are attentive to the overall effects of places, if they have a landscape gaze and not one tied to individual objects; otherwise, the gaze tied to architecture and the preservation of projects can only lament the ravages of time and nature without reading their life-giving power.

We must accept the fact that in the common sense of landscape, aspects of historical sedimentation are often read as deconstructed, reduced to ruin even before in thought than in matter, and that this process is not only a loss but also provides a suggestion for innovation and a seed for active interest in the complexity of the landscape.

[1] from A. Stifner, Abdia,1842 , Adelphi, Milan 1983, pg.13/15

[2] from M. Augè, Ruins and Rubble, Bollati Boringhieri, Turin 2004, pg.22

[3] see G. Simmel, Die Ruine, 1911, tr.it. in Rivista di Estetica, 8, 1981

[4] In On Modern Gardening, Walpole (the romantic of Otranto Castle and serendipity) makes William Kent’s principle his own in 1780: ‘Nature detests the straight line’, on which the design of the naturalistic garden is based. But for some time those characters were not only appreciated: for instance ‘For instance, nature apparently abhors a straight line, so all paths and avenues and streams were sent serpentining about in the most tedious and unmeaning fashion’ from Myra Reynolds, The treatment of Nature in English poetry between Pope and Wordsworth, Ams Pr Inc London 1909

[5] see R.Barthes , La camera chiara, Paris 1980, (Tr.it. Einaudi, Milan 1980).

[6] see P.Castelnovi, Il Senso del paesaggio (introductory report), IRES, Turin, 2000.

[7] v. P.Ricoeur, La Mémoire, l’Histoire, l’Oubli, Le Seuil, Paris, 2000; transl. it. La memoria, la storia, l’oblio, R. Cortina, Milan 2003.

[8] M.Belpoliti, Crolli, Einaudi Turin 2005

[9] ‘ There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus. It shows an angel who seems to be in the act of moving away from something on which he has fixed his gaze. His eyes are wide open, his mouth open, his wings outstretched. The angel in the story must look like this. He has his face turned towards the past. Where a chain of events appears to us, he sees a single catastrophe, which relentlessly heaps ruin upon ruin and throws it at his feet. He would like well to restrain himself, to raise the dead and reconnect the shattered. But a storm blows from heaven, which has caught hold of his wings, and is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm pushes him irresistibly into the future, to which he turns his back, while in front of him the heap of ruins rises towards heaven. What we call progress is this storm.’ from Theses on the Philosophy of History (Benjamin, 1940), tr. it (in Angelus Novus, Einaudi Turin 1962). There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus. It shows an angel who seems about to move away from something he stares at. His eyes are wide, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned towards the past. Where a chain of events appears before us, he sees on single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.

[10] v. C. Woodward, In Ruins, 2001; transl. it., Tra le rovine, Milano, Guanda, 2008

[11] see V. Guarrasi , Heterotopia del paesaggio e retorica cartografica, in Il senso del Paesaggio, cit.

[12] quoted by C. Woodward , cit.

[13] see Deleuze and Guattari, Rhizome, Pratiche, Parma, 1977